‘William Eggleston: Democratic Camera – Photographs and Video, 1961-2008’

@ The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

6th November 2008 – 25th January 2009

by Aaron Schuman

This essay was first published in Hotshoe International, February/March 2009.

In an attempt to summarize the basic philosophy behind The Democratic Forest, William Eggleston once stated, ‘I had this notion of what I called a democratic way of looking around: that nothing was more important or less important.’ As the recent retrospective at the Whitney, ‘William Eggleston: Democratic Camera – Photographs and Video, 1961-2008’, attests, such a perspective was not intended as a particularly rebellious or directly political attack on established hierarchies (after all, this is a gentleman who, despite his hell-raiser reputation, takes great pride in the fact that he has never owned a pair of blue jeans). Instead, Eggleston’s ‘democratic’ outlook is a rather traditional and thoroughly romantic understanding of the artist as, quite literally, a visionary, who can summon something out of nothing, or conversely, distil a fundamental essence from the chaos of everything. Over the course of nearly fifty years, Eggleston has shown that through the medium of photography, time, light, the physical world, and most famously color can be composed in such a way that it not only mesmerizes an audience visually, but also affects each individual emotionally, often in a profoundly subtle, primal and breathtaking manner.

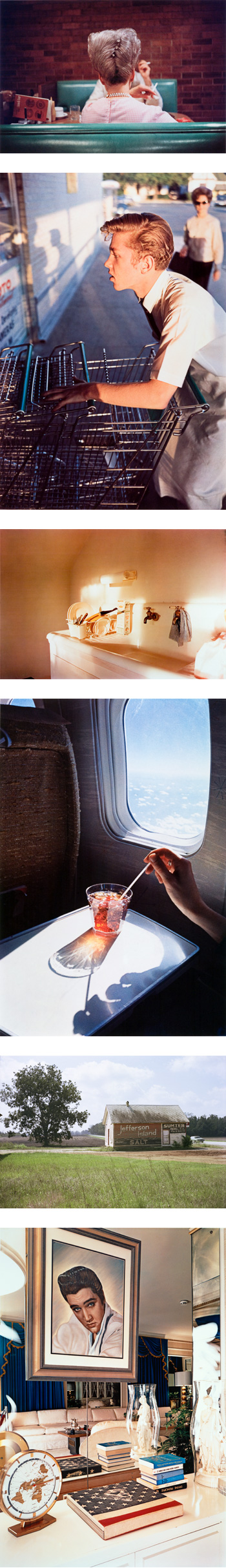

As with a distinctly potent piece of music, Eggleston’s compositions often possess a mysterious power that digs beneath the surface of things, excavating an otherwise indistinguishable mood or inconspicuous atmosphere; ultimately they move the viewer. The unexpected and playful joy found in a beehive hairdo, pearls and pink gingham as glimpsed from behind; the poised menace of a blood-red axe precariously perched on the edge of a barbeque; the soothing serenity of a sink and clean dishes drenched in golden sunlight; the piercing loneliness of a sparse hotel room haunted by the stark glow of a fluorescent strip-light mounted halfway down the wall – such feelings are often difficult to accurately recount, but they hit the viewer like a sucker-punch, and resonate deep within the pit of one’s stomach.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that, as a child, Eggleston’s initial passion was music rather than photography. ‘I would pass a quite fine piano in [my grandfather’s] house, every time I came from the back to the front,’ he reminisced recently. ‘It was in a big hall, and every time I went past it I would play a few things, notes, sometimes without any success at all. And then I got a little better and better. Time went on…and at a very early age I could play the piano. Anything, practically, after hearing it once…and maybe never play the same one twice. Very much like the way I optically work today.’ In fact, it wasn’t until the late-1950s, when a boy living across the hall in his university dormitory at Ole Miss (University of Mississippi, Oxford) showed him some pictures by Henri Cartier-Bresson, that Eggleston began to take the medium of photography seriously. ‘[They] were real art, period. You didn't think a camera made the picture,’ he recalls, ‘I couldn't imagine doing anything more than making a perfect fake Cartier-Bresson.’

Around the same time, Eggleston befriended Tom Young, a New York painter who was visiting Ole Miss as an artist-in-residence, and who was close friends with Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock and other Abstract Expressionists. Young and Eggleston began to socialize regularly, and even collaborated on an art piece in 1960, in which Eggleston built speakers into one of Young’s abstract sculptures, helped to design the accompanying audio, and assisted in its installation next to nearby railroad track. Although Eggleston hadn’t yet begun to seriously pursue his own photography - ‘I thought you had to go to Paris’, he remembers thinking – Young’s aesthetic, conceptual and creative influence made a lasting impression on his later work. ‘I love abstract painting,’ Eggleston noted in 2000, ‘I spent a lot of time looking at it. I bet that subconsciously it had something to do with what I was trying to get at.’

In fact, after leaving university (without graduating, despite having attended for five years – ‘I couldn’t see any sense in taking tests’, he explains) and marrying his childhood sweetheart, Eggleston did travel to Paris with his wife in 1964, but he didn’t take a single picture whilst there. Upon their return to the United States, the couple relocated to Memphis where Eggleston, looking for things to photograph, discovered that despite the city’s lack of obvious foreign allure, it nevertheless possessed something quite exotic: ‘What was new back then was shopping centers,’ he explains, ‘and I took pictures of them.’

The earliest photographs on show at the Whitney come from this formative period, and although they’re black-and-white, they reveal the beginnings of a distinctly original approach and unique personal style. Rather than doggedly pursuing Cartier-Bresson’s ‘decisive moment’ – ‘[T]he simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as the precise organization of forms which gives that event its proper expression’ – Eggleston’s initial photographic forays appear resolutely insignificant, imprecise and relatively uneventful. Whereas Cartier-Bresson danced balletically around city streets, ‘feeling very strung-up and ready to pounce, ready to “trap” life’, Eggleston seems to have ambled nonchalantly around convenience stores, suburbs, diners and car parks, at times not even bothering to get out of his car. Rather than the significance of an event or a moment, Eggleston’s images appear to be specifically about the making of photographs more than anything else. Whether it’s a young boy posing like a slouchy rebel in a donut shop, or a housewife’s eye catching the camera as she reaches for the passenger-side door of the family sedan, there is no implication that these images document, represent or even comment upon anything of consequence. Instead, they both emphasize and directly engage with notions of what it means to photograph, to be photographed, and to transform reality into an abstraction through the photograph; in the words of Eggleston’s contemporary, Garry Winogrand, ‘A photograph is not what was photographed, it’s something else.’

Furthermore, upon his arrival in Memphis Eggleston quickly involved himself in the city’s thriving cultural scene, and soon befriended William Christenberry, who was then teaching art at Memphis State University and often used his own small color snapshots as reference points for his drawings, paintings and sculptures. Eggleston was enamoured with the painterly qualities of Christenberry’s pictures, and in 1965 he began to experiment with color photography himself. And despite a few initial technical disasters with unstable and frustratingly insensitive film, he persevered. ‘I'd assumed I could do in color what I could do in black and white, and I got a swift, harsh lesson. All bones bared…Then one night I stayed up figuring out what I was gonna do the next day, which was go to Montesi's, the big supermarket on Madison Avenue in Memphis. It seemed a good place to try things out. I had this new exposure system in mind, of overexposing the film so all the colors would be there. And by God, it all worked. Just overnight. The first frame, I remember, was a guy pushing grocery carts. Some kind of pimply, freckle-faced guy in the late sunlight. Pretty fine picture, actually.’

This particular image is an outstanding example of how color infused Eggleston’s already accomplished photographs with an additional emotional weight and poetic power. Compositionally, the complexity of the picture would still be striking if it were only in black-and-white; the boy’s tender profile and impressively sculpted quiff take center-stage, but also cast a long, elegant silhouette onto a white brick wall to the left (along with the photographer’s own partial shadow), which is then visually counterbalanced by a similarly coiffured woman in cat eye sunglasses walking into the top-right corner of the frame. Yet, as Eggleston’s recollection of the image emphasizes, the ‘late sunlight’ is absolutely essential to the photograph, in that it sets a tone for the image – one of warm melancholy or wistful longing; a major chord, half-diminished.

Keeping both Eggleston’s painterly and musical foundations in mind, it’s interesting to note that the first Modern abstract painter, Wassily Kandinsky, once wrote, ‘Colour is the key. The eye is the hammer. The soul is the piano with its many chords. The artist is the hand that, by touching this or that key, sets the soul vibrating automatically.’ Throughout ‘Democratic Camera’, Eggleston’s exceptional color prints seem to possess just such a synethesic quality, each one humming from the wall and echoing throughout the galleries, creating a visual choir of sorts. Their vibrancy is due in large part to the fact that many of the works on exhibit are Eggleston’s original dye-transfer prints – a color-stable, pre-digital printing process used primarily for advertising in Eggleston’s day, which gives the photographer (in collaboration with the printer) complete control over the density, hue, saturation and tonal scale of each color within the image. ‘I was reading the price list of this lab in Chicago,’ Eggleston explains, ‘and it advertised “from the cheapest to the ultimate print”. The ultimate print was dye transfer.’ The transformative effect of this superior technology can be witnessed first hand when comparing several of Eggleston’s original drug-store work prints –displayed in glass cases at the center of one gallery– with their dye-transfer counterparts on the nearby walls. Most notably, a picture of a woman’s hand stirring an in-flight cocktail is turned from a washed out, ethereal, rather dream-like vision into a staggeringly sharp and radiant jewel, the drink heightened to a vivid ruby-red, which shimmers in contrast to the rich cyan sky seen through the plane’s window. It is in this transformation, Kandinsky’s assertion literally comes to light: color is the key.

Of course, the actual soundtrack for ‘Democratic Camera’ can be heard emanating from several monitors in one corner of the exhibition, where Eggleston’s infamous and fragmented video work, Stranded in Canton, is on continuous loop. Drawing together seventy-two hours worth of black-and-white footage made in 1973-4 – of Delta blues singers performing in backyards, eccentric Memphis night-owls delivering drug-fuelled rants, eerie studies of Eggleston’s own children, and so on – the piece again reflects brutally frank yet subtly romantic nature of Eggleston’s approach, presenting an uncompromising celebration of humanity, warts and all. In turn, these monitors are surrounded by larger-than-life, black-and-white prints from the same era, taken by Eggleston with a 5x7 camera in the small hours at various Memphis’s nightclubs. In contrast to the video’s primitive quality, these large-format portraits convert such back-room denizens into glamorous starlets, exaggerated icons, grotesque caricatures, fallen angels and demons writhing in ecstasy. Again, ghostly visions are clarified, amplified and sanctified through the photographic image alone.

Ultimately, “Democratic Camera’ confirms Eggleston’s profound dedication to the fundamentals of photography, whilst underscoring his enigmatic and often intentionally contradictory nature. From The Guide – which has bestowed invaluable creative guidance upon countless admirers without presenting any practical definition of what it’s actually guiding one through; to Election Eve – a assignment to photograph Jimmy Carter and his family for Rolling Stone, which stubbornly failed to feature the intended subjects, and was consequently rejected by the magazine only to be published as a limited edition box-set; from Graceland – a booklet sold to tourists visiting Elvis’s Memphis mansion by a man who stated, ‘I was never interested in Elvis. I’m still not’; to Los Alamos – a ‘secret lab’ in the form of a prolific photographic portfolio, that was rediscovered and published thirty years after its completion; Eggleston continues to thwart expectation and make work on his own quietly rebellious and often more rewarding terms.

Finally, ‘Democratic Camera’ demonstrates an admirable sense of respect, sensitivity and restraint on the part of the exhibition curators, Elisabeth Sussman and Thomas Weski. Today, Eggleston is a true American icon, and such a opportunity offers the clear temptation to produce an incredibly lavish, overstated, thoroughly merchandised blockbuster of a show. Yet, by elegantly downplaying their role, and hanging mostly original prints without any sense of pomp or pretense, Sussman and Weski allow the work to sing for itself; the genuine buzz within the room intimate, immediate, tangible and intensely powerful. As Memphis-based musician and producer, Bill Dickenson once said, ’That’s Bill to a tee…He wore Saville Row suits, and drove a Bentley, and played classical piano, but he was more rock'n'roll than any of us…He wasn't just at the party; he was the party.’

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2008. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.