Mitch Epstein: American Work

@ FOAM: Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam, June 29–September 19, 2007

by Aaron Schuman

Originally published in Aperture #192, Fall 2008

In his 1981 introduction to American Landscapes, John Szarkowski wrote: ”We have been half persuaded by Thoreau and by the evidence of our own brutal use of the land that the earth is beautiful except where man lives, or has passed through; and we have therefore set aside preserves where nature, other than man, may survive. . . . This is an admirable idea, and would perhaps be nobler still if we locked the gates to these preserves and denied ourselves entrance.” While pursuing his most recent photographic series, American Power (begun in 2003), Mitch Epstein has discovered that, within contemporary America, it is no longer nature that is granted such privilege; instead, it is our “brutal use” of nature that is aggressively protected. The clamorous police response to his presence as a photographer beneath the shadow of a West Virginian coal power plant reveals not only the pervasive influence of both corporate interests and paranoia in post–9/11 America, but also the resilient perception that photography constitutes a threat to security, and therefore retains its own mysteriously potent power.

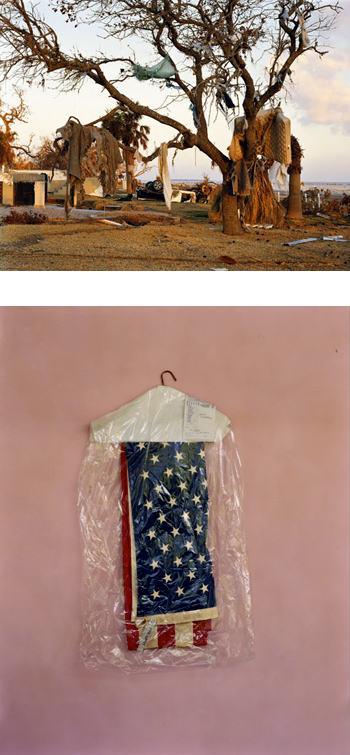

American Work, Epstein’s recent exhibition at the Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam (FOAM), showcased five grand prints from American Power. Despite the limited number, the selection revealed the diversity with which Epstein is both approaching and defining such “power”—from the use and abuse of natural resources, the societal implications of such actions and their subsequent environmental impact to the power of nature itself, and even that of sexuality within contemporary America. Epic in scale, rich in detail, Epstein’s compositions are easily located within the traditions of painting as well as those of photography. A couple beneath a tree near Niagara Falls—the woman gracefully wading out into the river, the man sitting on a rock, captivated by her gaze—invokes Titian’s Adam and Eve, or perhaps his Venus and Adonis with the gender roles reversed. A tree in Biloxi ravaged by Hurricane Katrina bears an eerie resemblance to Goya’s Disasters of War etchings, with their dismembered corpses strewn similarly among bare branches. Even the abstracted chimneys of Ohio’s Gavin Coal Power Plant emit churning plumes of smoke that mimic the brushstrokes of a windswept Van Gogh cypress.

As with the best visual art past and present, there is something physically palpable and deeply personal about these images, their compositional structures and textured surfaces evoking as much emotional response as their subjective content. Much contemporary large-format photography relies on scale, high vantage-point, and the precision of the medium to captivate museum visitors. But the best of Epstein’s photographs manage to hold the gallery wall like an Old Master work, luring one’s gaze through measured arrangement and subtlety of color, line, shadow, and texture.

In his earlier series Family Business (2000–03), also featured at FOAM, Epstein further revealed his artistic agility. Family Business documents the financial collapse of Epstein’s elderly father: a story of the American Dream leading one man to disillusion and despair. In its entirety (as seen in the monograph published by Steidl in 2003), the project is at its most dynamic, forceful, and moving. Yet even intensely edited and placed within the museum context, the images held the space. Again, allusions to fine art are evident, particularly to that of the American twentieth century—a fluorescent light bulb tucked into a corner hints at Dan Flavin; a flag, wrapped in plastic and hanging on a pink wall, riffs off Jasper Johns. But the more old-world, painterly intuitions of Epstein’s eye were not entirely absent here either: a portrait of the photographer’s swimming father—naked, arms spread wide, and literally sinking into the blackened water—hung at the far end of the galleries like a Pietà, an ever-present reminder of the martyr at the center of the surrounding tragedy.

Exhibited together, American Power and Family Business demonstrate Epstein’s remarkable ease in the public and the private realms, and also reveal what lies at the heart of his concerns as a documentary photographer, whether its effects are mutual or deeply personal. When asked why he is pursuing American Power, Epstein often responds simply: “I have a daughter”; and Family Business could easily be subtitled “I have a father.” But what the two projects share most is an intensive examination of a place, America, that appears to have transformed from a land of plenty into one of fear, greed, and devastation.

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2008. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.