'How We Are: Photographic Britain'

@ Tate Britain

May 22–September 2, 2007

Originally published in Aperture: #190, Spring 2008.

The British are famously keen on self-deprecation, that cunning double bluff whereby one’s attributes are subtly exposed and celebrated as they are simultaneously derided. How We Are: Photographing Britain from the 1840s to the Present, at Tate Britain, was an impressive exercise in that cunning balance between muted confidence and steady humility. Perhaps the participant who most accurately embodied the quirkily modest spirit of this exhibition was Charles Jones, a professional gardener and amateur photographer at the turn of the twentieth century. Jones’s affectionate and astonishingly beautiful gold-toned still-lifes of garden produce were entirely unknown until the historian, Sean Sexton, discovered five-hundred of his prints at a London street market in 1980, and began to put them into circulation. It’s as if a vast and forgotten Edward Weston archive – minus the egotism and modernist aspirations, and with a particular affinity for root vegetables – were to have turned up in garage sale last Saturday.

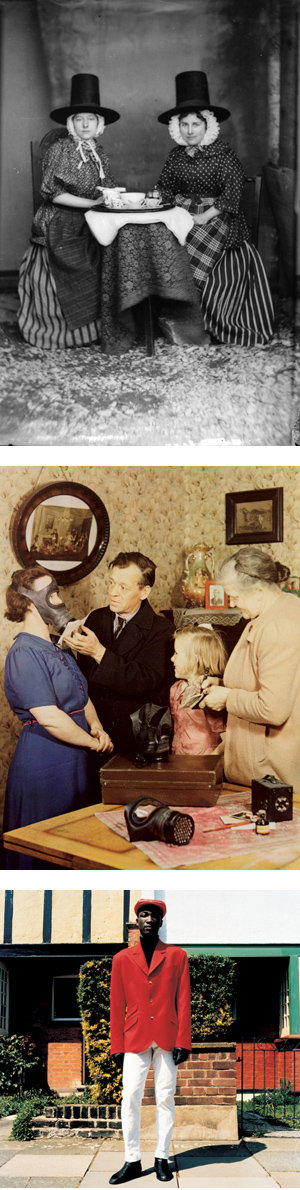

As the inclusion of Jones suggests, 'How We Are' - curated by Val Williams and Susan Bright - was clearly not a predictable survey of British photography; instead, it infused the traditional canon with pictures drawn from postcards, family albums, advertisements, instructional manuals, medical archives, criminal records, tourist publications, and more. What the curators described as “continuums” in the history of photography gained clarity and complexity as a vast array of intriguing parallels, juxtapositions and contrasts gradually surfaced. Zed Nelson’s contemporary portraits of British beauty queens possessed an unnerving resemblance to Hugh Diamond’s nineteenth-century studies of female psychiatric patients. John Thomas’s 1875 documentation of Welsh national dress—as well as the Lafayette Studio’s portraits of Edwardian royals at a costume ball—played cleverly against Martin Parr’s 1980s Morris Dancers, whirling in traditional garb in front of a McDonalds. And romantic visions of “England’s green and pleasant land”—asserted by Benjamin Turner’s topographical studies, Peter Henry Emerson’s survey of the Norfolk Broads, and Country Life’s 1961 Picture Book of the Lake District in Colour—were shattered by John Davies’s bleak industrial landscapes of the late twentieth century, and then reconfirmed by David Spero’s Settlements, an examination of the inventive eco-housing found in twenty-first-century alternative communities.

Throughout this process of reassessment and rediscovery, Williams and Bright exploited various provincialisms to their advantage, often using what might be considered unsophisticated imagery to make extremely sophisticated links between the years. By breaking down established hierarchies, they succeeded in democratizing the nation’s photographic output in a fascinating way, inviting the audience to discover for themselves the trajectory of this versatile medium over the course of nearly two hundred years.

That said, the chronological structure of the exhibition did expose a shift amongst British photographers as the medium matured, and as Britain’s view of itself changed with the onset of imperial and industrial collapse, recession, and globalization during the latter half of the twentieth century. The majority of pre-1960s photographs on display had a cool yet appreciative take on their subjects: vegetables, suffragettes, fishermen, and high streets are all treated with respectful consideration. But beginning in the late 1960s with Tony Ray Jones’s appropriation of American-style street-photography strategies, a certain satirical severity set in, which progressively abandoned the more empathetic approach of earlier generations. Tender documentation transformed into sharp critique as various photographers of the 1980s—Martin Parr, Paul Reas, Anna Fox, and Jane Bown among them—began to snipe away at the materialist pretensions and social hypocrisies that thrived during Thatcher’s regime.

Many of the contemporary practitioners included appear to have inherited a hint of this cynicism, although their imagery is generally subtler in tone. Fergus Heron’s 2006 Charles Church Estates series examines eerily bland suburbia; Jonathan Olley’s Deadman’s Point (2003) documents a holiday caravan park perched on the edge of a massive oil depot; Sarah Pickering’s Public Order project (2002-5) records the empty streets of a simulated urban environment, used by the Metropolitan Police for riot training. `

Today, many of Britain’s photographers have chosen to remain cautiously pessimistic, their work signalling a clear move away from assured self-deprecation and toward a sense of disorientation, apprehension and insecurity. Simultaneously collected and confrontational, this gathering of images revealed that today’s most critical wars are perhaps those we wage upon ourselves.

How We Are: Photographing Britain was on view at Tate Britain, London, May 22–September 2, 2007.

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2008. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.