The Mushroom Collector: In Conversation with Jason Fulford

by Aaron Schuman

Summer 2012

This essay was originally published in Aperture, Summer 2012.

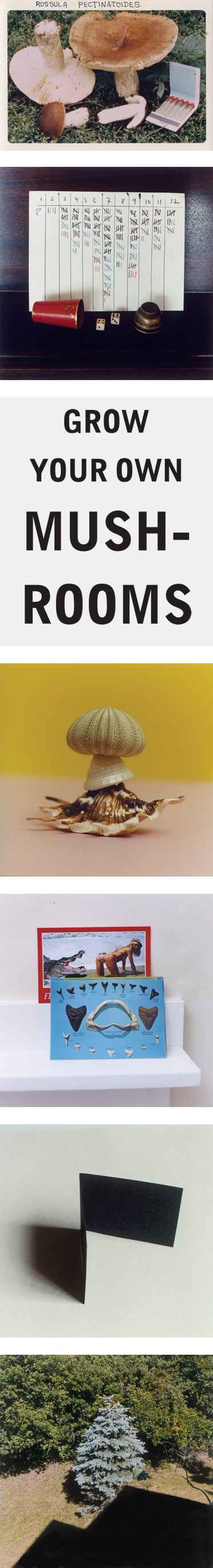

Jason Fulford is a photographer and co-founder of the U.S. publishing house J&L Books. In 2010, The Soon Institute (Netherlands) released his book The Mushroom Collector, a project that started when a friend gave Fulford a manila envelope, found at a flea market, full of anonymous photographs of mushrooms. The mushroom images stuck in Fulford’s mind, and then gradually started to grow in his own work. The Mushroom Collector, which combines the original flea market pictures with Fulford’s own photographs and text about the project, has since developed into “The Mushroom Collection”—an evolving series of publications, events, workshops, installations, and performances, the most recent of which was an exhibition and series of sculptural interventions at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts (October 21, 2011—April 8, 2012).

AARON SCHUMAN: Who is “The Mushroom Collector”?

JASON FULFORD: One of my favorite moments in literature is in a Flannery O’Connor story. The character strikes a match on his shoe, gazes into the flame and says: “Maybe the best I can tell you is, I’m a man; but listen lady, what is a man?”

AS: What is a mushroom?

JF: A mushroom is a spore-bearing fruit that pops up overnight and briefly decorates the forest floor. The Dutch call mushrooms “frog chairs” (paddestoel). John Cage said: “It’s useless to pretend to know mushrooms. They escape your erudition. The more you know them [ . . . ] the less sure you feel about identifying them.”

AS: From your perspective, what is the relationship between photography and collecting?

JF: The collector I’m thinking of is a scavenger whose mode is to wander. He enters the woods with an open mind. He might find a Scarlet Elf Cup or a Hen of the Woods; he may come home with nothing but an empty pack of cigarettes. The collecting happens over many years. The analogy continues when it comes to editing, making sense of the mess. Presentation is considered. Similar items are compared; the weak examples are discarded. The collector asks: Is there an audience for this? Is supplementary information necessary? Is the collection explanatory or mysterious? What ties the various elements together—the collector’s personal interests, or a predetermined set of categories? Is it about repetition or variety? Does the collection continue to grow, or is it now closed?

AS: In The Mushroom Collector, the images, the interplays between text and image, and the sequence in which they are presented act as visual puzzles. Furthermore, within the photographs there are subtle but direct references to games and puzzles throughout (dice, balls, jacks, and so on), and in “The Mushroom Collection”—various installation pieces and that have been presented around the world—you’ve asked the audience to engage in games. Quite literally, this work is quizzical and puzzling in nature. What is the importance of puzzles and games to you?

JF: Photography has clarity in the same way that language has. A word is precise, but its meaning can change based on the words around it: think tank, tank top. When a person looks at a photograph you’ve taken, they will always think of themselves, their own life experience. They will relate your photograph to their memories. That interplay is where a picture becomes alive and grows into something. It’s different for every viewer.

My puzzles don’t have definitive solutions. I guess they function more like invitations. I saw a roadside attraction in Northern California recently: on the gate was a sign that read: “If you came here to have fun, you will, if not you won’t.”

AS: In a sense, you’re dependent upon a wholly collaborative relationship, and much of “The Mushroom Collection”—in its various incarnations—relies on the active participation of all who are involved; it’s a team effort. Photography is so often considered an independent, individualistic (sometimes lonely) pursuit, but you manage to instill a communal spirit in much that you do.

JF: You’re right, there is collaboration on every level. First, between the people who inspire me and affect the way I see the world. Then, between myself and my audience.

A few years ago, my friend Ted Fair found a manila envelope at a flea market in Manhattan. Inside were eighty-nine color photographs of wild mushrooms. He gave them to me and I loved them. I took them out every couple of weeks, spread them out on a table, then packed them up again and put them into a drawer. A year later, going through recent contact sheets, I noticed that a relationship had been growing between the mushroom photographs and my own photographs, without my realizing it. That moment of realization was the initial spark for this project. When art succeeds, I think, it stays alive this way—an idea or a sensibility or perspective is passed on from one person to another, and in the process, it changes a little.

AS: In William Eggleston’s Guide (1976), John Szarkowski writes: “Whatever else a photograph may be about, it is inevitably about photography, the container and the vehicle of all its meanings. [ . . . ] Photography is a system of visual editing [ . . . ] Like chess, or writing, it is a matter of choosing from among given possibilities, but in the case of photography the number of possibilities is not finite but infinite.” With The Mushroom Collector you are acting as photographer and editor, scavenger and collector. So if the gathering of material is unregulated and intuitive, how do you first go about “making sense of the mess,” as you put it?

JF: In this case, there was a linear thread. An evolution. And it was personal. The structure became apparent when I studied the mess; the challenge was how to communicate that structure to an audience. The visual sequence for The Mushroom Collector was determined first, and was quite abstract. To soften this and add another layer, I wrote a text that reaches out to the reader on page one and leads you through in a more personal way.

AS: And then, how did the book ultimately take shape?

JF: Several years ago, working on a different project, I started a ritual of traveling to a neutral location for important editing sessions. It helps to focus attention, and also adds an unexpected flavor to the work. The editor of The Mushroom Collector, Lorenzo De Rita, and I decided to meet in Istanbul. We spent a week walking through underground cisterns, riding ferries, getting lost, and talking about mushrooms, fathers, garbage trucks, and the pleasures of chaos. At the end of the week, we had found a direction for the book.

AS: Many of the images in The Mushroom Collector contain a subtly rigorous formalism, with modernist references, whereby the subject is transformed by or takes a backseat to The Photograph, the medium itself, and your engagement with it as The Photographer. But a couple of images—such as the one of an open car trunk filled with cabbages, with a row of shoes in front of it—stand out as slightly looser, more personal, more emotive, and perhaps more free from the rigors of both your eye and the medium.

JF: Often when a new body of pictures begins to take shape, I will look back through my archive to see if there are any images that foreshadow the new idea. That picture was made in 1999, when I lived in Hungary. I’d crossed the border into Romania and wandered into a flea market. This “seed” sat dormant for ten years until the Mushroom project started to grow.

AS: In a conversation about the 1967 New Documents show at the Museum of Modern Art, Joel Meyerowitz stated that Lee Friedlander’s work was “coolly intellectual [ . . . ] He's more cerebral than Diane [Arbus] or Garry [Winogrand]. They were capable of being dispassionate, even detached. But the hard truths of their needs and urgencies and personalities are what made their photographs so astonishing. Lee's pictures are less astonishing to me—their complexity hits me first. [His images] coolly crept up on you, their delights just came slower, through a different intelligence.” Do you consider your work more cerebral than emotive, or are there personal, intimate, “urgent,” or even sentimental elements embedded in it?

JF: The work I want to make has a specific mix of cerebral and emotive. I want you to use your whole brain. The balance shifts, back and forth, like you’re on a boat. I love the fact that humans invented logic, but are unable to apply it pure to their lives. I love moments of faulty logic, e.g. A=B and B=C, therefore A=C.

AS: In exhibition form, The Mushroom Collector has evolved into “The Mushroom Collection”—an ongoing metamorphosis of objects, games, narratives, and ideas raised in the book, which has taken the form of a living-room/storefront (Amsterdam), a pop-up basement darkroom (New York), a scavenger hunt in a bookshop (Los Angeles), and a selection of sculptural interventions installed within a museum’s permanent collection (Minneapolis). How do these productions relate to the essence of (or philosophy behind) the initial book project, The Mushroom Collector?

JF: This entire project has evolved in a very natural way since the beginning. After the photographs were edited into a book, the publisher asked me to come to Amsterdam for the release. There happened to be a vacant storefront down the street, and we decided to present the book in the space. Since it was a storefront, we turned the book into a store and exhibition. Prints and contact sheets were displayed alongside objects that had inspired the book. When I returned to the States, I was invited to organize a one-day event in New York, in the basement space of Dexter Sinister. There are no windows, so we turned the space into a darkroom. When the Minneapolis Institute of Arts asked me to present the work, it became a museum exhibition. There is a logic to it.

AS: The latest incarnation of “The Mushroom Collection,” at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, takes the form of both a photographic exhibition and a series of sculptural interventions within the museum’s permanent collection of more than eighty thousand objects, which represent five thousand years of human creative endeavor around the world. Could you describe the interplay between your photographs—your original collection—and theirs? Furthermore, how does your work change when it's embedded within an existing collection, and how does their collection—or at least its meaning—change thanks to your intervention?

JF: “The Mushroom Collection” pops up only when the conditions are fertile. With each new iteration, it grows somehow. In the assigned gallery at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, images from The Mushroom Collector have been enlarged, framed, and arranged on the walls in combinations that suggest relationships. There are two videos that play in a dim side-room. A selection of the original flea-market photographs of mushrooms hangs on the walls in a haphazard arrangement. The gallery serves as the sort of “home base” for the exhibition, and the mushrooms make their way out into the other galleries, causing mischief.

With photography, I’m interested in how one image can affect your reading of another. Similar dialogues happen between objects in this exhibition. For example, Harriet Hosmer’s Medusa (1854) has been turned to face a mirror on the wall. A wooden jigsaw puzzle has been placed into a vitrine of sculptures from Papua New Guinea. A shell, balancing a wooden ball on its head, faces off with Man Ray’s Gift (1921/63). A ceremonial bow and arrow from Benin are lit with red, green, and blue lights. I hope that visitors to the museum will first find connections within my own work, and then continue on through the museum, finding relationships between their own lives and art from all the collections. I’d like to inspire that spirit of investigation.

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2012. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.