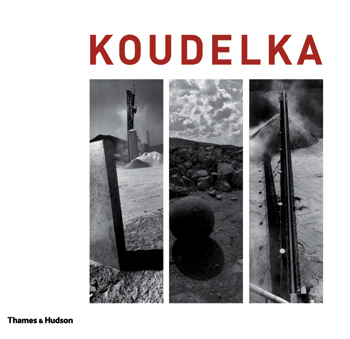

Koudelka (Thames and Hudson, 2006)

by Aaron Schuman

October 2006

by Aaron Schuman

Originally published in Hotshoe International, December/January 2007

In the forty-five years since his images were first exhibited, Josef Koudelka has contributed a diverse and inspiring range of work to the photographic canon. Many of us first knowingly encountered Koudelka’s brilliance in Gypsies (Delpire/Aperture, 1975), a portfolio of stark intensity and astonishing empathy, which explored a dispossessed community living at the borders of civilization. Nine years later, we learnt that the ‘anonymous Czech photographer’ behind the startling photographs of the 1968 Soviet invasion of Prague - famously smuggled across the Iron Curtain and into the hands of Magnum – were also by Koudelka, a fact finally revealed once the threat of reprisals against his family ended with the death of his father. In 1988, Koudelka again challenged and mystified us with Exiles, an intentionally poetic and lyrical examination of alienation, desolation and loneliness as manifested in general contemporary existence. And finally, in later works such as Chaos and Camargue he adopted a panoramic approach, using the landscape itself to explore political and cultural deterioration, manmade environmental destruction and nature’s own insistent regeneration. Koudelka has remained an enigmatic presence throughout, peering deep into the shadows at the furthest edges of society, and simultaneously out from those shadows, into the heart of history. ‘There are only great photographs, not great photographers,’ he has famously exclaimed. Yet, Thames and Hudson’s stunning new monograph, Koudelka, insists otherwise. With astutely edited selections from his most famous projects alongside lesser-known examples of the his earliest work, we are offered half a century’s worth of great photographs, and also given insight into what exactly makes Koudelka himself a truly great photographer.

The earliest photographs in the book – first exhibited at Prague’s Semafor Theatre in 1961 – reveal sincere artistic aspirations, rather than explicitly journalistic or political intensions. Exposing a strong affinity for Modernist aesthetics, they toy with line, form and abstraction more than with the ‘documentary’ possibilities of the photography. Yet, what these visual experiments do share with Koudelka’s later, more celebrated work is a distinct respect for the power of austerity. Distant silhouettes hover over bleak horizons, balancing on what seems to be the edge of existence, and one gets the sense that Koudelka’s eye was attuned to itinerancy, exile and chaos long before he even considered pointing his camera at more literal examples of such experiences.

After exhibiting his work at the Semafor, we learn that Koudelka quickly gained commissions from theatre companies and publications, and hence an introduction into the evidential as well as the expressive potential of photography. ‘With us he learned to see theatre as life, which also led him to see life as theatre,’ notes Otomar Kreja, the director of Prague’s Divadlo Za Branou (Theatre Beyond the Gate), one of the first companies to invite Koudelka to photograph dramatic performances. There is no doubt that the ramifications of this lesson appear in the following chapters – ‘Invasion, Prague 1968’, ‘Gypsies’ and ‘Exiles’ – in which the abstractions of bullet-torn facades, cracked and crumbling plaster and forbidding landscapes recede into the image, acting as a backdrops for the theatre of humanity itself. In nearly every one of these photographs, the borders of Koudelka’s frame appear as edges of a stage; the subjects come forward, hit their mark and relentlessly appeal to the audience before them. Like Checkov or Beckett, Koudelka manages to extract a sense of poignancy from the inevitability of the everyday, and finds heartrending drama resonating within even the subtlest of details.

To a certain extent, ‘Chaos’, the final chapter of Koudelka, marks a departure from this strategy, in so much as most of the actors disappear, and the landscape itself simultaneously becomes both stage and central character. Panorama has too often been abused by photography – frequently reducing extraordinary vistas to flat, inarticulate planes of focus – so much so that the format is almost instantaneously dismissed by those serious about the medium. Yet, as one would expect, Koudelka’s visual dexterity prevents him from falling into such a trap. Drawing on lessons learnt in some of his earliest Modernist experiments, Koudelka takes great advantage of the diagonal, calling on wayward roads, twisting paths, snaking rivers and meandering, manmade constructions to lead the viewer deep within the frame. Instead of sitting passively in the stalls, here we find ourselves forcibly engulfed by the set of life itself; a landscape left in ruins, both deeply disturbing and seductively sublime. In doing so, Koudelka ultimately appeals to our own faculties of vision, experience and understanding, and acutely involves us in his own.

‘Estragon: Charming spot. Let's go.

Vladimir: We can't.

Estragon:Why not?

Vladimir: We're waiting for Godot.’

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2008. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.