RYAN MCGINLEY (b. 1977) lives and works in New York. He enrolled at Parsons School of Design in 1995, and made a name for himself with ‘The Kids Are Alright’, his raw and intimate photographs of friends in downtown Manhattan at the turn of the millennium. McGinley’s work has appeared in many publications, including Index, W, Vice, ID, Dazed and Confused, The Fader and New York Times Magazine. At 24, McGinley became the youngest artist to have a solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and his work has continued to be exhibited internationally, at venues such as P.S.1, Galerie du jour Agnès b., FotografieMuseum Amsterdam (FOAM). In 2007, McGinley received the prestigious ICP Infinity Young Photographer Award was honored by the Guggenheim Museum’s Young Collectors Council. McGinley’s latest series, ‘I Know Where the Summer Goes’, was presented by Team Gallery in May, - a monograph of his work, Ryan McGinley, will be published by Twin Palms in Autumn 2008.

AARON SCHUMAN is an American photographer, editor, lecturer and critic based in the United Kingdom. He received a B.F.A. in Photography and History of Art from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts in 1999, and an M.A. in Humanities and Cultural Studies, from the University of London’s London Consortium in 2003. He has exhibited his photographic work internationally, and has contributed to publications such as Aperture, ArtReview, Modern Painters, Foam, OjodePez, HotShoe, Creative Review, The Face, DayFour, The Guardian, The Observer and The Sunday Times. He is a Senior Lecturer and Research Fellow in Photography at the Arts Institute at Bournemouth, and a Lecturer in Photography at the University of Brighton. Schuman is also the founder and editor of SeeSaw Magazine. For more information, please visit : http://www.aaronschuman.com/

This interview was originally published in Hotshoe International (#153 - April/May 2008):

http://www.hotshoeinternational.com/

AS – Aaron Schuman

RM – Ryan McGinley

AS: Firstly, how did you get into photography?

RM: I grew up skateboarding, and when I was fifteen years old I bought a digital video camera. I started to make films of my friends doing tricks, but soon realized that I was more interested in the in-between moments, where everyone was just hanging out; people’s personalities kind of shined. So I started editing those moments into the films. It was still about landing the trick, but it was also about just hanging out. I think that my photographic approach today is still very similar to how I made those films. There’s a lot of repetition to get the right photograph, and it’s always about strong personalities.

AS: When did you decide to make still images rather than videos?

RM: I stopped skateboarding when I moved to New York; it was onwards and upwards to art. I attended Parsons, but photography wasn’t offered to me during the first year, and if I can’t do something I want it more than anything, so I was always looking at the photography kids’ pictures. They fascinated me. I was only familiar with photography through snapshots, and actually I never took pictures growing up. Also, my family never took pictures of me growing up. I’m the youngest of seven siblings, so the kids before me were completely documented in super-8 films and photographs, but then for some reason my parents just gave up with me. There’s no evidence that I ever existed. So looking at those students’ photographs really put a new thought in my head. Then in my second year I started studying graphic design, and I had to incorporate photography into some of the projects. So I started taking my own pictures.

AS: Did you ever go through an ‘experimental’ phase with photography, or did you always photograph your friends?

RM: No, I always shot people. At the time I was living on Bleeker Street, and my apartment was like a flophouse. There was lots of people coming and going, hanging out late, staying over. Everyone was doing drugs, everyone was having sex, and everyone was willing to be photographed. We were a really tight group of people, and even though everyone was aware of the camera, they weren’t scared of it. So I started making documentary photographs of what was going on. Mostly I shot at night, because we just kind of slept through the days.

AS: When did you start to take other photographers’ work seriously?

RM: For about six months I just made photos. But then I realized that I was really interested in photography and should probably learn more about it, so I started studying its history. Someone had told me about William Eggleston, so I looked at his work, but I just didn’t get it. Then I looked at Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, and I was blown away. I just couldn’t believe it. I could relate to it so much – it was about New York, it was about downtown, it was about a bohemian lifestyle, and it felt very close to home. That was a big influence.

AS: Even within Goldin’s most joyous images there’s often a hint of sadness, pain or melancholy – there’s a bittersweetness to them. But your work is utterly positive - almost euphoric. Did the darker side of Goldin’s work resonate with you at all?

RM: That wasn’t my life. I was 19 years old, having a great time, and just photographing everything. The Ballad spans a long period of time, but I was making my photographs during a few incredibly fun years, so I guess that’s the spirit that came through in my photographs. And it’s still the spirit I want to pursue. I’m not making documentary photographs anymore, but I’m still interested in positive energy, freedom and rebellion.

AS: Your description of the Bleecker Street flat reminds me of previous downtown scenes in New York; the Beats, Warhol’s Factory and so on. Were you aware of that past – the bohemian traditions within The Village and the Lower East Side, and that spirit of the ‘urban commune’?

RM: Not really. I took an Allen Ginsberg class in college and was somewhat familiar with Warhol, but it wasn’t contrived in that way. We weren’t consciously following that tradition. We did it because we wanted to. We were just having fun and making art.

AS: In 2000, you put on your first exhibition, ‘The Kids Are Alright’, at 420 West Broadway. How did that come about, and were you aware of the history of the building, in terms of the art world, when you organized the show?

RM: Yeah, sure. The first time I went to 420 West Broadway, I saw a Gilbert and George show, so I was definitely aware of the building’s importance in the art world. But by the time I had my exhibition all of those famous galleries had moved out. A friend of a friend’s father owned the building, and we all went in there one night just to hang out. He told me that they were going to tear down the building and turn it into luxury lofts in about six months. I was with my friend, Jack Walls - who was Robert Mapplethorpe’s lover and model - and he suggested that I put up a show there. A few days later, I approached the owner of the building and he said, ‘Do whatever you want with it,’ so I made around sixty giant prints for the show, then made invitations and passed them around town.

AS: You created a hand-made book for the show as well.

RM: Yeah. I was still studying graphic design, and was very familiar with desktop publishing. Also, affordable negative scanners had just come out and I got one right away. It was amazing; all of a sudden I had a darkroom on my desktop and it changed my life. So the book ended up having around fifty pages. I printed a hundred of them on the Epson printer, and had an assembly line of friends helping me – we stuck them together with double-sided tape. About thirty sold at the show, and then I distributed the rest to galleries, to magazines and to artists that I admired.

AS: How did ‘The Kids Are Alright’ go from being a small, self-produced book and exhibition to a solo show at the Whitney?

RM: Well, I sent out the hand-made books and the first people to call me back were Index; they started giving me assignments right away. It was crazy because I was just a junior in college, and to have my name in their roster with photographers like Wolfgang Tillmans, Richard Kern, and Juergen Teller was so exciting. Then about three months into working for Index, they established Index Books - a publishing company for art books - and they said, ‘Your book is already done, you have it all on the computer, and we really love it. Why don’t we publish it?’ The turnaround was really fast; I think it took about three weeks. The readership of Index was an art-oriented crowd, and wherever Index was available my book was available, so a lot of people in the art world got it. Eventually it ended up on the desk of Sylvia Wolff, the curator of photography at the Whitney. She came down to my studio – well not my studio, my bedroom – and I pulled photographs out from under my bed. I showed her what I was working on that summer. I was doing a series of people skinny-dipping in Coney Island, and since 1998 I had made a portrait of everyone that had come into my apartment, just against a white wall with a Polaroid camera. She was interested, so she offered me a show.

AS: After the Whitney show, you left New York for a little while.

RM: Yeah, during the first seven years that I lived in New York I only left maybe once or twice, just to go home and visit my parents. But I never wanted to leave. I was so happy being in the city – riding my bike around, making photographs, going to parties and staying out all night. Then in 2002 I went upstate with a group of friends for a few days, and there was something about it that really inspired me. I grew up playing in the woods near my suburban neighborhood, but I’d kind of forgotten about it. Going upstate reminded me of being a kid, and having this sense of freedom out in nature. I also noticed that something happened to my friends, like they left something behind in the city – this weight on their shoulders. So after the Whitney show, in 2003, I decided to do something new. A collector had a house in Vermont that he never used, and he said to me, ‘Feel free to go up there whenever you want.’ It was this amazing house, a chateau in the middle of nowhere with so much property. So I decided to go to there for the summer, and went back and forth between Vermont and the city, bringing friends up that I wanted to photograph.

AS: Did being away from the city make documentary photography more difficult, in the sense that, without much going on, did you feel that you needed to make things happen?

RM: Well, I started setting up situations in 2002. I’d find a location, have some ideas, give people some direction, and then would let them be free within those boundaries. It was nice because they were photographs that I wanted to make, but at the same time I still wasn’t sure what I was going to get. It was so exciting to give people some direction, but then let them run free; their personalities would take over and they would offer me something that I could have never expected.

AS: Were you casting people based on your concepts?

RM: No, it was just who was available. Most of my friends were artists, musicians, actors, and so on, and nobody had jobs. So we would just go up there and make photographs. It was perfect because there was this great house, and the woman who took care of it, Joy, took care of us too. She’d feed us, and buy us cigarettes and booze. We were all sort of her children.

AS: There’s certainly a more childish spirit within that work. The city photographs evoke a feeling of teenage rebellion – the joys of mischief, debauchery and experimentation. But in the countryside your subjects seems to regress even further into childhood; it becomes more about innocence and freedom, like when you’re a toddler and it’s just pure fun to take off your swimsuit and dance around naked.

RM: Yeah, sometimes we were naked all day, and there was an instant bond. When you’re naked you can’t hide anything, and you become very close with people incredibly quickly. It was amazing, and I started to think about what kind of images I really wanted to make. I started to have a different approach.

AS: What did you look to for inspiration?

RM: Lots of things – amateur photographs off the internet, nudist publications, stills from movies that I liked, photography annuals.

AS: So many great American photographers have adapted both vernacular and commercial photographic strategies – amateur snapshots, postcards, old magazines and so on – for their own creative purposes. American photography in particular seems to rely on the influence of more everyday photography.

RM: Yeah, about a week ago I was at dinner with Dr. Ruth, the sex expert. She wasn’t familiar with my photographs, but they sat her next to me because they knew that my work was about sexuality. She asked me, ‘What does your work look like?’ And I said, ‘Well, if you take the everyday things that people do in nudism, vintage pornography, and Sports Illustrated, and you mix them all together, you’ll get an idea of what my photos look like.’

AS: And what was her response?

RM: She said, ‘I get it!’

AS: After your time in Vermont, you started to go on extended photographic road-trips in the summers. What inspired you to go on the road?

RM: In that same year that I did the Vermont work, Mike Mills invited me to take stills for his film, Thumbsucker, and I had this epiphany on the set. Mike had a cast of actors, and a whole team of people working with him. They jumped from location to location, they shot every day, all day long, and got so much accomplished in such a short period of time. I realized that there were a lot of elements within filmmaking that I needed to incorporate into my work in order to take it to the next level. Also, Mike said to me, ‘Ryan you should make a film’, so I started writing a screenplay. I did so much research and got interested in making a road-trip movie – something like Easy Rider. I spent a lot of time on the screenplay in 2004, but I kind of wrote it in a backwards way. I would use my ideas for images as the storyboard, and then would write the screenplay based on the images. Eventually, I realized that I wasn’t ready to make a movie yet, but I knew that I could make the pictures, so in 2005 I organized a trip and went cross-country for three months with about ten subjects. The first trip was very haphazardly planned out, in the sense that we had some locations in mind, but we also went where the road took us. It became like a rock band, or a family, or a tribe. I was really happy with the results when I got back, so I’ve continued to organize a road-trip every summer since.

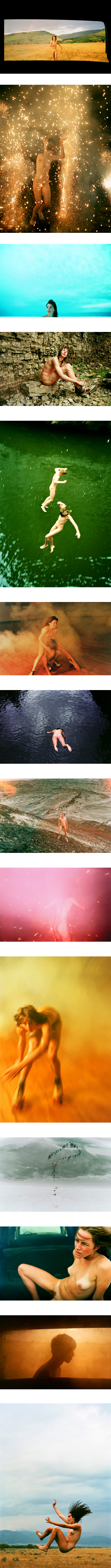

AS: A lot of your road-trip images are overexposed or completely blown out, and there are often light leaks, sun flares, shifting colors, and double exposures. Again, you’ve incorporated a wide range of ‘flaws’ or ‘amateur mistakes’ into this work, but their consistency and effect points to the fact that their not mistakes at all.

RM: No, they’re not mistakes. I want my photographs to be accessible, and I want people to feel that they could have almost taken the pictures themselves. I want the viewer to be reminded of a place they’ve been, or of an experience that they’ve had themselves; then they can come to their own conclusions. But it takes a lot of work to make successful photographs that also look very free, easy and spontaneous. This summer we were shooting at Great Sands, in Colorado. We walked about a mile into the dunes and had been shooting for about fifteen minutes when I looked up, and the sky was black. So we started running back to the car, all naked, and suddenly it began to hail. Everyone was getting pummelled, then lightning started to strike all around us, and some people even began to cry. Finally we all made it back safely. Then the next day there was almost a mutiny within the group, because I said, ‘We’ve got to go back there. I only shot for fifteen minutes, and I didn’t make photos that I was happy with.’ Everyone was shouting, ‘You’re crazy! We’re not going back!’ It was like a Hertzog situation. But finally I convinced them to go back, and we made some photos that I was really happy with.

AS: In your most recent work, you incorporate a lot of smoke and fireworks.

RM: When I photograph people I want them to be preoccupied, so they’re really not aware of my camera. I do everything possible to distract them. When someone is running around, or jumping, or falling, or rolling down a sand dune – and then you add smoke or fireworks to that – the subject is forced in their own world. They become very natural, and also there’s a sense of disorientation.

AS: I’ve been on several road-trips across the States and was often harassed, particularly by small-town police officers, for taking photographs. Did you ever get in any trouble with the law?

RM:Yeah, I got arrested last summer. There were seven people naked, blasting on jetskis. The Coast Guard went by us and then we heard the sirens. They just looked at us like, ‘What the fuck is going on? What is this?’ No one had life vests; no one had licenses for the jetskis; and the speed limit was 35 – we were doing 70. Actually, I made a really nice photograph of it, but we all got arrested. Also, this summer we had a close call. I was photographing this naked girl in a hotel corridor, and a woman opened her door. She screamed, ‘Oh my god, I’m calling the cops!’ So the police came. I explained that I was a fine art photographer, and broke out my credentials. Also, I had recently shot Kate Moss for W, so I eventually showed them those photos. They said, ‘Oh man, you shot Kate Moss! She’s so fucking hot!’ So I smoothed it over that way; I guess my credibility went up.

AS: You just turned thirty, or you’re about to – is that right?

RM: I’m about to turn thirty. Oh no, wait – it’s my birthday today! I keep forgetting.

AS: The reason I bring it up is that your photos are very much about the joy and freedom of being young. Many artists continue to focus on youth as they grow older – Larry Clark is still making both films and photographs about teenagers well into his sixties – and I was curious if you see yourself continuing to focus on young people as you grow older?

RM: I don’t think so. I think that my ideas will start to change as I do. I’d still like to make a movie, but I don’t think I’m ready just yet. My master plan is to do two more years of these road-trips with some smaller projects in between, and then I’ll start to focus on film. I had a long discussion with Gus Van Sant about making movies the other day, and he said, ‘You gotta do it. Just start looking at the stuff you’ve already done, and instead of having a camera that makes photographs, have a camera that makes films.’ I always film everything anyway, especially photo-shoots, so I think I’ll start by editing that footage and then take it from there.

AS: Well, Happy Birthday, and thanks so much for your time and generosity!

RM: Yeah, it’s been cool. Thank you.

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2008. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.