Just That Much Beauty Was Gone: Yuji Obata’s Winter Tale

by Aaron Schuman

September 2009

This essay was originally published in Photoworks, Issue #13, Autumn 2009.

It seems a strange paradox that, in order to perceive, study and even celebrate the ephemeral nature of things, humanity invented a technology that lends a sense of permanence to that which would otherwise quickly disappear. In 1839, upon discovering a means by which to make a lasting photographic negative, William Henry Fox Talbot wrote, ‘The most transitory of things, a shadow, the proverbial emblem of all that is fleeting and momentary, may be fettered by the spells of our “natural magic”…Such is the fact, that we may receive on paper the fleeting shadow, arrest it there, and in the space of a single minute fix it there so firmly as to be no more capable of change, even if thrown back into the sunbeam from which it derived its origin.’ Much of the language that accompanies photography acknowledges the apparent endurance that occurs when it is applied to the world – ‘still’, ‘fix’, ‘lock’, ‘stop’, ‘freeze’ and so on – yet very rarely does the medium concede that what truly lies at its heart is not the arresting of time, but rather time’s passing.

In 1880, a fifteen-year-old farm boy in Jericho, Vermont was given a microscope by his mother, and soon became fascinated by the flurries of snowflakes that surrounded him during the winter months. Five years later – after much experimentation with a small blackboard used to catch the falling snow, and a large-format camera affixed to the end of his microscope – Wilson ‘Snowflake’ Bentley successfully photographed a single snow crystal for the first time, and subsequently made more than five thousand images of snowflakes over the course of his lifetime, noting that that no two were ever alike. ‘Every crystal was a masterpiece of design,’ he noted, ‘and no one design was ever repeated. When a snowflake melted, that design was forever lost. Just that much beauty was gone, without leaving any record behind.’ One should also note that snowflakes are truly ethereal in that they not only melt when exposed to temperatures above freezing, but also, at subzero temperatures, turn from solid into gas without passing through a liquid phase – a process known as subliming.

In 1930, Ukichiro Nakaya, a young assistant professor in physics, arrived at Hokkaido University in Japan’s northernmost prefecture, an institution that at the time had limited equipment and funds, but an overabundance of snow. Inspired by Bentley’s photographs as well as by the Hokuetso Seppu, or ‘Snow Stories’ – a nineteenth-century encyclopedic collection of the customs, dialects, industries and folk tales of Japan’s ‘snow country’, which includes early sketches of snowflakes – Nakaya chose the subject as the focus of his research. He began to photograph snow himself, and eventually created the first artificial snow crystals in 1936; three years later he established the Japanese Association of Snow and Ice, famously musing, ‘Snowflakes are letters sent from heaven.’

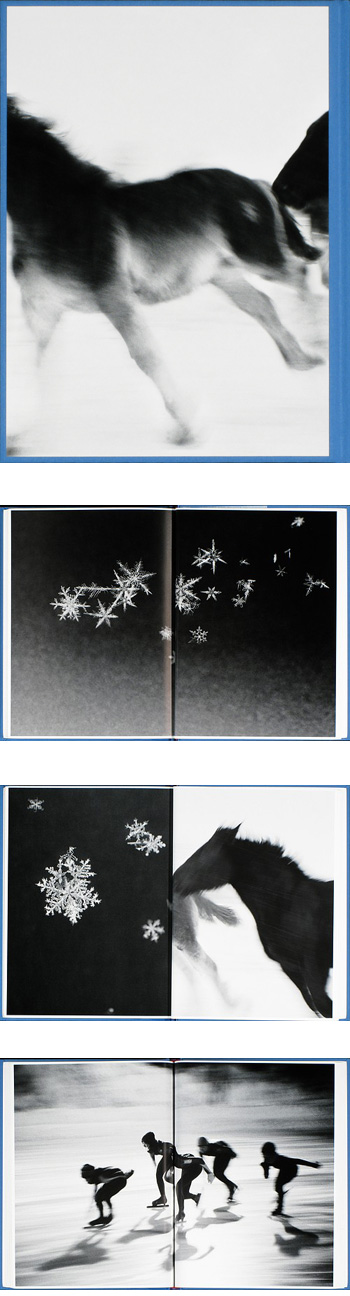

In 2003, inspired by a drunken conversation about ice-skating with a barman from Hokkaido, and a subsequent encounter with Pieter Breugel’s painting, The Hunters in the Snow, the Japanese photographer, Yuji Obata, ventured north to Hokkaido himself to photograph speed skaters within the wintry landscape. Whilst there, he too became mesmerized by the snow, its effects and its singular, jewel-like, vanishing perfection as it fell upon his coat and across his car’s windshield. With his work on the skaters complete, Obata nevertheless continued to make visits to the region, turning his camera toward other hibernal phenomena – the invigorating blur of windblown flurries, icy lakes and wintry landscapes, children sledging, factories steaming, horses galloping through snow-white showers and, having discovered both Bentley and Nakaya in his research, crisp close-ups of snowflakes themselves as well as the cabin where Nakaya studied. The resulting monograph, ‘Winter Tale’ (Sokyu-sha, Tokyo, 2007), is a charming meditation on the frozen yet fleeting nature of the season, collecting together Obata’s diverse observations in a poetically puzzling manner. Subjectively and stylistically, the images seemingly lack a traditional sense of consistency (as many have observed, typological studies have both propelled and plagued photography, past and present), and both the unorthodox variety and unpredictable sequencing at first lead the viewer towards a state of curious confusion. Yet gradually, as one accepts the mercurial temperament of Obata’s vision and recognizes the underlying tone of the book, each individual photograph gains weight and importance, captivating the viewer with its uniqueness and own sense of sublimity. And then, with every turn of the page, each image disappears from the mind’s eye as quickly as it arrived – like ‘letters sent from heaven’, one gently learns to savor one at a time, and becomes aware that no two are ever alike.

Of course, despite its best efforts and the rather convincing illusion that it creates, photography itself is as transient as a shadow or a snowflake. Fox Talbot’s original negative – now kept by the National Photography Collection in a light-tight case under lock and key – is unable to be exhibited today; if it were to be ‘thrown back into the sunbeam from which it derived its origin’, the image would itself sublime, disappearing into thin air within minutes. Obata’s lyrical and captivating tale serves as a poignant reminder of the beauty of impermanence and change, and also reassures photographers that despite the ultimate futility of their medium, their efforts are not in vein. ‘Unless a verse is by one whose very being has been transfixed by the truth of the impermanence and change of this world, so that he is never forgetful of it in any circumstance,’ wrote the fifteenth-century Japanese poet, Shinkei, ‘it cannot truly hold deep feeling.’

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2009. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.