Not Any More: Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s 'Thousand'

by Aaron Schuman

Originally published in Foam, Winter 2007

By the mid-1970s, the suggestion that photography lent itself more to fiction than to fact was by no means a new one. In fact, the adoptive godfather of American documentary photography, Walker Evans, regularly railed against the naïve notion that the art of photography lay in its ability to document, noting that, ‘A document has use, whereas art is really useless. Therefore art is never a document, though it certainly can adopt that style.”

Nevertheless, throughout the twentieth century the vast majority of photographers have founded their work upon such a style, and have relied on the collective understanding that, if a photograph is not the objective recording of reality, it is at least a representation of truth, however subjective that representation may be. It was only when Conceptual artists began to use photographs to record, represent and reinterpret staged events and invented scenarios in the 1970s that photographers themselves began to abandon the frontlines of reality for them medium’s storytelling capabilities. Finally, they grasped the idea that to consciously make images, rather than to take them, could be a compelling and arguably a more honest approach to photography.

Steeped in the art-school culture of the era, and having pursued a Masters degree in photography at Yale in the years directly following the death of Walker Evans – the department’s founding chair – Philip-Lorca diCorcia was one of the first photographers to turn Evans’s strategy on its head. Rather than adopting a ‘documentary style’, diCorcia chose to style documentary, explicitly appropriating the fictive techniques of fashion, advertising and commercial photography to construct narratives, or to imbue reality with a heightened sense of otherworldliness. For many, the application of a polished and rather glossy aesthetic to what was meant to be serious, critical art-photography was a profound betrayal of established traditions. But diCorcia wholeheartedly rejects the notion that a medium as diverse and accessible as photography must submit to such single-minded conventions. ‘More so than a lot of people, I think that I’m concerned with how an image looks - the production values, or whatever you want to call it,’ he explains. ‘It’s always seemed rather shameful to me how easy photography is. So I’m not someone who makes a virtue of spontaneity, or willfully disobeying the “rules”. But then, how can you disobey the rules of something that had no rules to begin with? It’s ridiculous.’

Today, diCorcia is generally celebrated for his meticulously produced series, in which he creates a tightly controlled scenario or setup, and then explores variations on a theme within its rather strict limitations. Looking at the totality of diCorcia’s serial work, it becomes very clear that his output is remarkably diverse. Yet, perhaps because of their seductively polished appearance, the substance of diCorcia’s imagery is often overshadowed by its accomplished technical prowess. His oeuvre has occasionally been falsely regarded as uniform simply because of its distinctive appearance, and its variety in both content and methodology has often gone ignored. One might assume that such misreadings would frustrate diCorcia, but having gained a mature understanding of how practical trends are eventually subsumed by more important concerns, diCorcia remains both confident and firmly optimistic about the future of the medium. ‘Since the advent of digital, the idea of how an image is made has almost superceded what it is. People who cobble together dozens of images in a computer, or spend thousands of dollars to produce a single image, are a novelty at the moment. But they’re a quickly disappearing novelty, and sooner or later, it’s going to come down to what they do, rather than how they do it.’

Paradoxically, when the content of a diCorcia’s work is taken into consideration, it is generally interpreted based on the preferred genre or critical disposition of the individual viewer, rather than on the artist’s overall intentions. ‘People tend to think of me according to which body of work they like best,’ he says. For those inclined towards diaristic developments within art photography, his ‘Family and Friends’ series serves as the ideal alternative to the grainy confessionals of others. (The simple fact that diCorcia attended the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston – alongside the likes of Nan Goldin and David Armstrong – often serves as the crucial supporting evidence for this association). For those invested in traditions of street photography, diCorcia’s ‘Streetwork’ introduces an intriguing spin on the assumed realism and spontaneity involved in photographing a kinetic, urban public. Likewise, his ’Heads’ series could fall into the same camp, or could alternatively be interpreted as a novel approach to photographic portraiture, in which the implicit relationship between photographer and subject is all but dismantled. And for those who acknowledge the propensity of ‘concerned’ documentary photography to focus on outcasts, the downtrodden and the sordid underbelly of society, diCorcia’s ‘Hustlers’ cleverly mimics and simultaneously critiques the stereotypically romantic depictions of such social extremes. Despite the occasional accusations aimed at diCorcia of gimmickry, uniformity, superficiality and frivolity in relation to his style, the content of his serial work appears to be both diverse and remarkably flexible, repeatedly offering valuable insight into the most integral concerns within photography today.

In his essay, “Ways of Remembering”, John Berger remarks, ‘Before the invention of photography what served in its place? The obvious answer would be engravings, drawings, paintings, graphic works of one kind or another. Yet, if one doesn’t look at it from a purely technical point of view, what served the function that photography now serves…was the faculty of memory.’ Several years ago, diCorcia momentarily abandoned his serialistic approach in order to develop a more personal book project, challenging preconceptions of both his technique and methodology. A Storybook Life consists of seventy-six pictures, taken over the course of twenty years, which bear little obvious relationship to one another. Consciously avoiding his inclination to produce subtle variations on a controlled theme, diCorcia intentionally edited the project in a disparate manner, exploring the narrative possibilities of a seemingly ambiguous but in fact carefully considered sequence. Bookended by images of diCorcia’s father – the first taken when he’s alive, the last when he’s dead - A Storybook Life certainly touches on themes of personal experience and memory, but the intimacy of such meanings remains veiled behind the vagaries of diCorcia’s photographic eye. As Andy Grunberg has noted, ‘Despite his ongoing interest in unpredictable, psychologically charged subject matter, diCorcia does not wear his heart on his sleeve.’ Instead, as Berger intimated, through photography itself the book simulates the general experience of memory. Seemingly insignificant moments, turning points in one’s life, and even convincingly realistic fantasies intermingle to create a complex but thoroughly confusing representation of a life as it might be remembered. Interviewed in 2003, diCorcia reflected, ‘My ten-year-old son recently asked me, “Dad, do you think that people really remember everything that happened in their life before they die?’ And I said, “I don’t think they remember everything, but yeah, I’m sure that your life flashes before you. And I’m also sure that it doesn’t happen in the right order, and things that didn’t seem important probably get priority over one’s benchmarks.”’

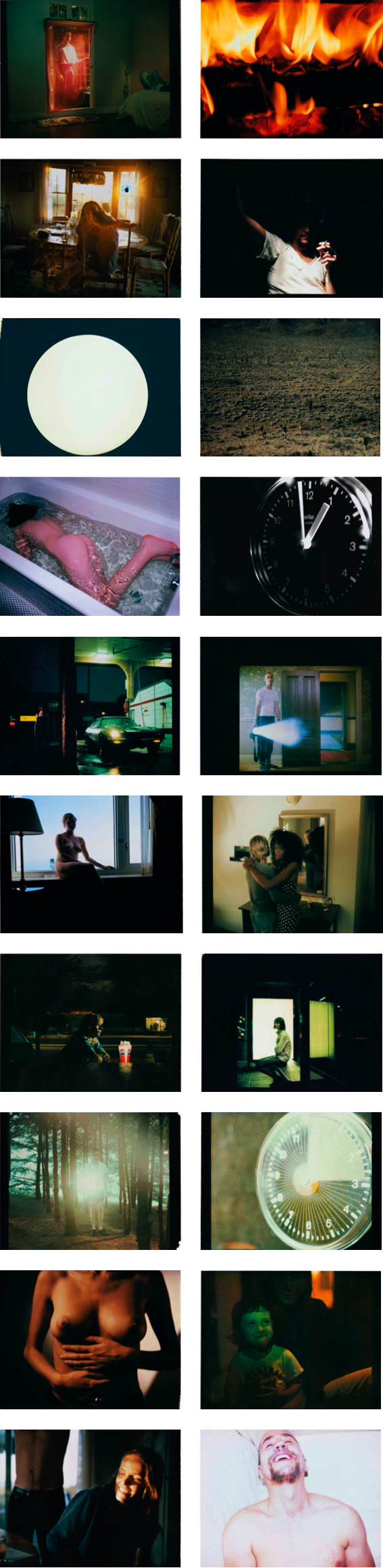

diCorcia latest book, Thousand, takes the experimental promise of A Storybook Life to a new and challenging extreme. Having accumulated nearly four-thousand Polaroids over the course of the last twenty-five years – both in the production of his serial works, and through the making photographs outside of set projects – diCorcia edited his collection down to a thousand images that, for one reason or another, felt strong enough to be included in the book. Originally, the idea was to assign each Polaroid a number, and then to allow a computer-generated sequence to randomly determine the order of the work. But as diCorcia gradually fed groups of images to his producer for scanning, he notice unexpected relationships developing between entirely unrelated images. ‘It both encouraged me and discouraged me to edit,’ he explains, ‘and it was a struggle to let circumstance dictate the order. That was the original intention, but I figured that we’d eventually fool with it later anyway, and the whole thing would be a lie. So in the end, I spent a week editing them.’ That said, a thousand photographs is more than anyone can digest or organize in any realistic amount of time – whether they are deeply familiar with images or not – and the resulting tome is vast, unpredictable, incredibly frustrating and addictively engaging. There are elements of formal, emotional and subjective repetition throughout – circles factor highly, there’s an uncharacteristically large selection of self-portraits, fire appears to play an important role within the work, and clock-faces seem to carry an integral significance. As these rather mysterious themes rise to the surface, along with many others, they tempt the viewer into a false sense of insight and perception. But as quickly as they emerge, they suddenly disappear, driving one to obsessively dig further into the book’s pages in search of the slightest suggestion of purpose or meaning.

Although A Storybook Life hinted at the diversity of human experience seen through the filter of memory, it still represented a distilled and relatively concise interpretation of this concept. Alternatively, Thousand both encapsulates and reenacts the barrage of information that one encounters over the course of a lifetime, relentlessly overwhelming the viewer, and denying them the comfort of reflection or understanding. ‘The nature of experience is similar to the book,’ observes diCorcia. ‘In life, people have a very hard time seeing the overall picture; it’s too complex, and it’d probably kill them if they did see it. Yet, every once and a while one catches a glimpse – you see that we’re on a planet, in a solar system, in a universe that is ever-expanding, and you can actually imagine that. But you have to force yourself to think about it, and a lot of other little things that get in the way. There’s just too much information, and its hard to know whether one thing is more important that the other.’

Again, considering that the only obvious aspect which draws this work together is the fact that they are all Polaroids, it is tempting to be seduced by diCorcia’s technical choices rather than by his overarching concept. Of course, diCorcia bluntly rejects this interpretation, remarking, ‘To use a toy camera is about as much of a statement as to not clean your underwear.’ Nevertheless, in relation to his previous work, there is something telling about diCorcia’s use of a volatile and unpredictable format; it conveys a newfound pleasure uncertainty and loss of control, and provides a refreshing contradiction to his more famous bodies of work. ‘I think that every photographer has, at some point, complained that the final product didn’t looks as good as the Polaroid,’ diCorcia says. ‘One of the things about Polaroid is that it’s not like a print – they don’t make it perfect. Sometimes you find yourself saying, “That’s close enough,” or “Oh no, it came out all purple…but I like that.” I would never do that myself.’ In a sense, Thousand represents a deliberate liberation on diCorcia’s part, in which the tightly woven constraints of his serial work are forsaken, and his practice is allowed to flourish in an entirely new, spontaneous and immensely rewarding way. “For someone who has to go through a lot of arranging of both equipment and situations, Polaroids are very gratifying. I think that’s what people like about photography compared to most other mediums – it’s quick. I’ve always considered that as one of the things which I’ve been missing out on.’ Not any more.

Thousand, by Philip-Lorca diCorcia, is published by Steidl (2007).

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2008. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.