Sublime Proximity: In Conversation with Richard Mosse

by Aaron Schuman

Originally published in Aperture, #203, Summer 2011

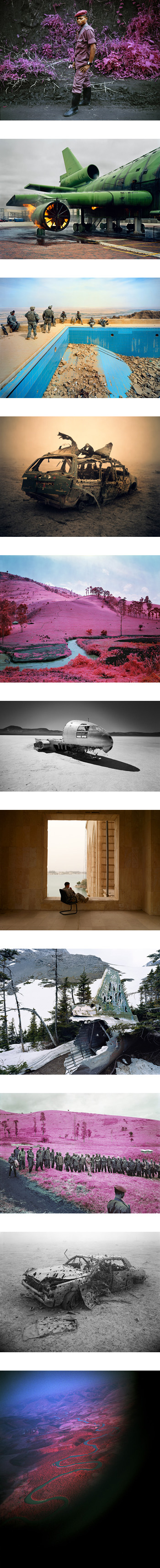

Over the course of the last seven years, Irish photographer Richard Mosse has photographed postwar ruins in the former Yugoslavia, cities devastated by earthquake in Iran, Pakistan, and Haiti, the occupied palaces of Saddam Hussein, airport emergency-training simulators, the rusting wreckage of remote air disasters, nomadic rebels in the Congolese jungle, and more. Reading through his catalog of subject matter, one could easily assume that Mosse is an inveterate photojournalist in the most traditional sense, chasing hard facts in order to illustrate breaking news. Yet through his work—generally photographed in large format and presented large scale, with a penchant for the staggering, the allusive, the historical, and the Sublime—Mosse is revealed as a practitioner intent on challenging the orthodoxies of documentary photography, in particular the contexts, imperatives, and “responsibilities” that are often both assumed by and imposed upon the documentary genre, and indeed upon the photographic medium as a whole.

AARON SCHUMAN: How did you first become interested in photography?

RICHARD MOSSE: I come from a family of artists. My grandfather was a sculptor, my uncle is a painter, and my mother studied at Cooper Union under Hans Haacke, so becoming an artist was very natural. My parents are potters, and photography seemed like a kind of antidote to that. Its light-sensitive simulation is at a far remove from ceramics, so I took to it at an early age. Shards of pottery that were formed from earth by hand will outlive us all, unlike photographs, which will perish in the sunlight that they once traced. Photography allowed me to be an artist without working in anyone’s shadow. That’s especially the case in Ireland where the medium is not so celebrated, in spite of seminal work by Willie Doherty, Paul Seawright, Donovan Wylie, and others.

Initially I was drawn to cinema as a teenager, and became obsessed with the French New Wave. But I found the military-style hierarchy of working in a film crew unsatisfying, so gave up filmmaking and concentrated on my degree in English literature. I dug deeper into a career in academia, getting a Masters in Cultural Studies at a left-field institution called the London Consortium—a research body formed in the interstices between the University of London, Tate, the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), and the Architectural Association. Studying there gave me the freedom to integrate my own photographs into a written examination of the postwar Balkan landscape, and things evolved from there.

AS: How did that academic experience influence your subsequent pursuit of photography?

RM: I think it’s important that photography is cut through with other disciplines and a wider understanding of the world. Though I loved spending my days in the university’s library, a life in academia seemed removed from lived experience. I wanted to be a maker rather than a critic, a producer rather than a consumer. Photography is an engagement with the world of things, and it has given me a genuine pretext to travel widely and experience what James Joyce called “good warm life.” I’m most excited when there’s an elision of the critical and the creative in my work, so I haven’t discarded my academic foundations. Instead I try to build on them.

AS: The first time we corresponded, in 2003, you quoted Sol LeWitt: “When words such as painting and sculpture are used, they connote a whole tradition and imply a consequent acceptance of this tradition, thus placing limitations on the artist who would be reluctant to make art that goes beyond limitations.” You then wrote: “Yet I've always insisted on using photography. I think something is about to shift.” Has this “shift” occurred yet—for you, or for photography in general?

RM: At the time I wrote that I was working at Art Monthly, a British art magazine. I wasn’t yet fully practicing as an artist. I was the listings editor, consuming gallery press releases all day long—the best art education possible. Sol LeWitt’s statement now seems slightly tautological. Perhaps a better quote to answer your question might be from Robert Adams: “Photographers have generally been held to a different set of responsibilities than have painters and sculptors, chiefly because of the widespread supposition the photographers want to and can give us objective Truth: the word ‘documentary’ has abetted the prejudice. But does a photographer really have less right to arrange life into a composition, into form, than a painter or sculptor?”

Where LeWitt uses the word traditions, Adams says responsibilities. How much more limiting are your traditions when they are saturated with a moral imperative? The photographer is expected to be “responsible,” but responsible to whom? Documentary photographers whose work bears some relation to photojournalism are particularly constrained. Their expressive arteries have been hardened by years of World Press Photo Awards and the shadow of the intrepid photojournalist sporting a scarf and a Leica. Where would we be if Robert Frank had hidden his Leica in a scarf?

AS: So do you see your work as part of an evolution of photojournalism? And if so, when you find yourself at a hotel bar in Baghdad or Beirut, surrounded by traditional photojournalists, what discussions take place? I know that you’ve got the dusty, weathered boots . . . surely you must have a scarf and a Leica in your wardrobe somewhere as well?

RM: I found myself in Haiti this spring, shooting for a news magazine. It was my first editorial commission, and I ended up back at the hotel bar each night deeply confused, trying to reconcile my instincts with what I felt was expected of me by the editors. Two photojournalists—Jake Price and Scout Tufankjian—rallied to my side. They pointed out that the editors only wanted me to do exactly what I do; they wouldn’t have hired me otherwise. It was so simple, but I couldn’t see that without their help. I find working alongside photojournalists can be very inspiring. They work incredibly hard and are deeply committed. They also make excellent drinking partners.

AS: How do you decide upon your subject matter—is it driven by research and theory, which then leads to a search for the physical manifestations of your underlying idea in the real world, or vice versa?

RM: My process is very intuitive. The idea must come first, but the process of making the work becomes a pursuit of that idea—a “quest,” or more usually a kind of staggering picaresque narrative. My journeys are often very problematic, unplanned, and full of failure. For example, earlier this year I wanted to use a highly unstable infrared film technology as a way of thinking through the conflict in Congo. My concept was very raw and underdeveloped. Embarking upon the journey, I found myself challenged in many ways, not least because I had no knowledge of moving through this difficult land, and no experience of using this type of film. I was dealing with the unknown, negotiating my own ignorance. Since infrared light is invisible to the human eye, you could say that I was literally photographing blind. As soon as I arrived in Congo I had crossed a threshold into fiction, into my own symbolic order. Yet I was trying to represent something that is tragically real—an entrenched and endless conflict fought in a jungle by nomadic rebels of constantly shifting allegiances.

The actual situation that I discovered in Congo became folded into the initial idea, and I began to find ways to interpret what I encountered on my journey through this conceptual, logistical, and technical precariousness. Over time, these failures became synthesized into a kind of epiphany. I had privately reached a kind of messianic state where I could no longer perceive the absurdity of my task. So the research and theory adhere to, and become ramified by, an initial driving intuition.

AS: Your work bears more than a slight resemblance to artistic movements that directly preceded the invention of photography, such as Romanticism and history painting. These movements were eventually overtaken by Realism in the nineteenth century, and photography—as both a technology and medium—seems to have, until recently, been aligned more with Realism than with Romanticism. Do you think that a Romantic approach to photography is appropriate within contemporary practice?

RM: Photographic realism has become so inscribed upon twentieth-century depictions of war that we often forget that there were other forms before it: the panorama, the history painting, even 3-D spectroscopic views of the battlefield. In the past, this is how the public understood their wars—as distant sweeping landscapes of enormous scale and detail. I feel that early war photographers like Mathew Brady and Roger Fenton were influenced by these precedents. But they were soon forgotten with small-format technologies, and with changes in the way that wars were fought during the twentieth century. Warfare is constantly evolving; it has recently become abstracted, asymmetric, simulated. We are so removed from the experience of war in the West that I feel the genre may shift once more. The realist forms that were so powerful throughout the twentieth century may now be obsolescent.

In my practice, I struggle with the challenge of representing abstract or contingent phenomena. The camera’s dumb optic is intensely literal, yet the world is far from being simple or transparent. Air disasters, terrorism, the simulated nature of modern warfare, the cultural interface between an occupying force and its enemy, the martyr drive in Islamic extremism, the intangibility of Eastern Congo’s conflict—these are all subjects that are very difficult to express with traditional documentary realism; they are difficult to perceive in their own right. Very often I am fighting simply to represent the subject, just to find a way to put it before the lens, or make it visible by its very absence. This process is inherently “Romantic” because it often requires a retreat into my own imagination, into my own symbolic order.

But the real is central to my interests, as it’s something that eludes conventional genres, particularly Realism. The real is at the heart of contemporary global anxiety; proximity to the real is endured by us all. But I feel that the real is only effectively communicated through shocks to the imagination, precipitated by the Sublime. That may seem like an archaic term, but what I’m referring to here is contemporary art’s unique ability to make visible what cannot be perceived, breaching the limits of representation.

AS: When you first arrive at a location—a U.S. military base, a Congolese village, etcetera—and explain your intentions, what’s the response?

RM: I’m always surprised by how generous people are when they encounter my photographic handicap, the view camera. The people on the ground who watch me set up my tripod and unfold my bellows are generally more aware of the significance of my subject than I am. The problems are usually encountered further up the line, with press officers, spokesmen, lawyers, corrupt officials, red tape. My journeys occasionally lead me into abject situations and Groundhog Day–style cul-de-sacs. For example, on a recent trip to Ethiopia my guide got us lost on the Eritrean border, a recent war zone. Our vehicle’s four-wheel-drive malfunctioned, and the engine overheated constantly. The driver stopped every half-hour to pour tinned tomato puree into the radiator to cool it down. Then we were tricked by Afar tribesmen with Kalashnikovs into taking the wrong road, which we traveled for days, ending up in a refugee camp. My crew feared potential intertribal violence so we decided to sleep in the police station. When we finally approached our destination the Land Cruiser’s tires got stuck in the desert sand, the seven armed guards who were traveling with us started to fight with the cook, the driver fell asleep, and our guide began to pray. I had to dig the vehicle out of the sand. We never reached our destination. It was an invigorating jaunt, but not a sustainable way of life.

AS: In the past two decades, there has been a wave of what is often referred to as “aftermath” photography. Would you regard your own work as a part of this movement?

RM: Aftermath photography took everything interesting about the New Topographics and turned it into a movie set. Thankfully, there’s a place for these photographers . . . it’s called Detroit.

AS: But how do you differentiate your images of Iraqi or Serbian ruins from those of the many photographers who have flocked to Detroit or post-Katrina New Orleans to photograph debris with heavy tripods and large-format cameras?

RM: Guilty as charged. Although even if some of my work is similar in form to aftermath photography, I do feel there is a distinct difference in both my approach and intent.

For the Romantic poets, the ruin carried tremendous allegorical power, and that power resounds today in contemporary photography. Perhaps the ruin’s absent totality signifies something very different to us now than it did back then—its timeless resonance shifts for each generation. Nevertheless, we are still drawn to the same imagery that Caspar David Friedrich was. I’m not so sure that we’re always honest with ourselves about this fascination.

The thing that strikes me about a lot of aftermath photography is the moral high ground that the photographers often take. Their journey into darkness becomes a kind of “performance of the ethical”; witnessing the catastrophe becomes an act of piety, of noblesse oblige, when in fact it’s nothing of the sort. I would imagine that most aftermath photography is really just an artist’s quest to find meaning and authenticity through extreme tourism. I’m reminded of the poète maudit, the Romantic antihero who will go to the ends of the earth and transgress all moral boundaries for the ultimate aesthetic experience. This irresponsible, self-destructive rogue was best embodied in the crapulent, wayward lives of artists like Arthur Rimbaud or Paul Gauguin. The “responsibilities” that Robert Adams complained about, abetted by the documentary, seem to preclude the maudit in photography.

AS: Is the notion of “spectacle” important to you?

RM: Last summer I found myself trespassing in an abandoned, war-damaged hotel near Dubrovnik. I tinkered about this Brutalist ruin with my camera, finding various Yugoslav relics from 1991, the year that the hotel became a front line in the fighting between Serb snipers and Croat militias. Then, as I was making my way through the wreckage, I noticed a modern cruise ship anchored in the nearby waters. This huge luxury vessel mirrored the hotel in form; the parallel between the two vast structures was uncanny, and I began to think about their relationship. Placed alongside each other, what sort of dialogue did they open up? The cruise ship, I reasoned, is an unmoored signifier of globalization par excellence, its tourists comfortably numb within their air-conditioned matrix, blissfully ignorant of the traces of war facing them on the cliff. The ruined hotel, on the other hand, spoke of local tribal enmities, of painful regional memories, of conflict and war. I meandered to the conclusion that perhaps war is the only remaining hurdle standing in the way of global amnesia; perhaps war is the only thing that redeems historical narratives in the face of this leveling of identity.

These thoughts followed me back to New York, where I developed the rolls of film that I’d shot in Croatia. On my contact sheets I discovered one image depicting shattered mirrored steps, broken beer bottles, fake flowers, and a hangman’s noose on a dusty ballroom floor. This photograph seemed to mock my fallacious theory about war, memory and the consequences of globalization. I’d dreamed that the evocative ruin represented an alternative to the society of the spectacle—that I’d trespassed in the forbidden wreckage of the real. I flattered that afternoon’s adventure as some sort of original transgression of the spectacular. But the souvenir document that I’d returned with reminded me that the hotel’s bombed-out ballrooms were also the occasional haunt of local ravers. International DJs come with smoke machines and strobe lights and use the place as an exotic live venue, appropriating its authentic war remnants as a stage for hipsters to celebrate their alienation.

I was reminded of Guy Debord’s words. The spectacle, he writes, “is the sun which never sets over the empire of modern passivity. It covers the entire surface of the world and bathes endlessly in its own glory.”

The monograph Infra, by Richard Mosse, is published by Aperture (2011).

'Sublime Proximity - In Conversation with Ricard Mosse'

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2011. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.