Malick Sidibe: 'Chemises'

@ Foam - Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam

13th June - 15th October 2008

by Aaron Schuman

This essay was first published by Aperture, Issue #193, Winter 2008

Several days after being mesmerized by Malian photographer Malick Sidibé’s recent exhibition Chemises (Folders) at the Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam (FOAM), I received an email from a friend describing a New York party: “[It] was serious: a Long Island City backyard on an exceedingly humid New York night, with beach balls hitting the turntable causing record needles to skip, and friends making out with friends they shouldn't be making out with.” Strangely, Sidibé’s small index prints of 1960s Malian revelers—slightly faded and crookedly glued to administrative folders (chemises)in careful sequences—filled my mind’s eye, superimposing themselves upon my imaginings of my friend’s twenty-first-century hipster do. It occurred to me that the psyche of partying has changed little over time. And for the second time that week, I marveled at the visual acuity, intimacy, and lasting vitality of this unique photographer’s phenomenal catalog.

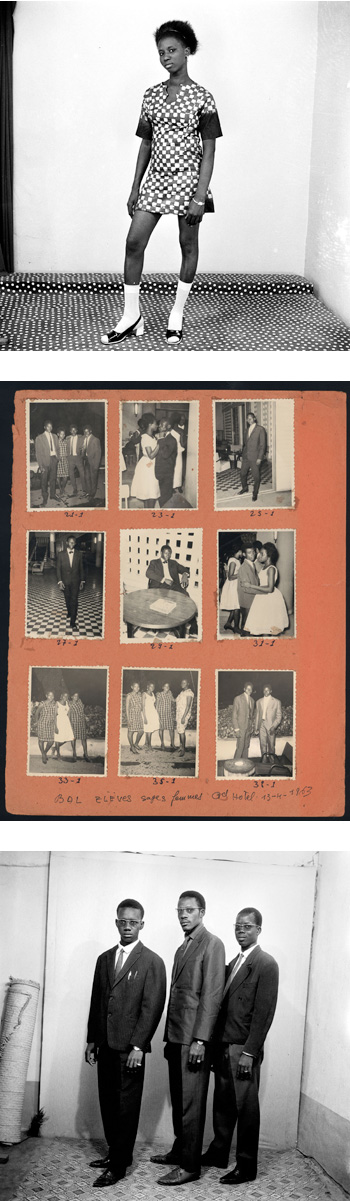

From the late-1950s to the mid-1970s, Sidibé documented social events, weddings, baptisms, and most notably the vibrant, post-independence nightlife of Bamako, photographing the parties held by various “clubs” in the city each Friday and Saturday. His presence itself gained great significance within these tightly knit social circles; as he explains it: “People said if [I] was at a party, it gave it prestige. I would let people know I’d arrived by letting off my flash. . . . You could feel the temperature rise right away.” Although they may look rather quaint by today’s standards— Miles Davis and James Brown LPs providing the skipping 1960s sound track for couples doing the Twist—there is certainly a hint of feverishness in the images, due in part to the sexual tension that has always permeated such gatherings. Throughout the various sequences, men and women hold each other tightly, proud to be in each other’s arms before the camera. As one series progresses through a lively August evening in 1962, nine different boys manage to pose with what must have been the prettiest girl in the room; in another, from March 1963, a straw trilby migrates from the head of a dapper young man to that of a gorgeous woman, whose dress prominently bears the portrait of Mali’s first president, Modibo Kéïta—a romantic coup on the part of the admirable young Casanova. Sidibé’s shrewdly recognized that pop music was liberating the urban youth, specifically by providing them with an opportunity to dance intimately with members of the opposite sex. “Especially for the young men,” he says, “it was a very powerful moment to be seen dancing close with a girl”; or to put it another way: “For us, touching a girl was like touching gold.”

Appreciating the immediate charge of such alchemic moments, and the inevitable demand for evidence of them, Sidibé would often rush back to his darkroom at five a.m., as soon as the parties finished. By the following Monday morning, hundreds of small, quickly printed photographs were displayed in files on the walls of his studio—just as they are in Chemises, and as they are faithfully reproduced in a brilliant monograph of the same title published by Steidl—so that the club kids could swing by, peruse the files, reminisce about the previous weekend’s events and conquests, and perhaps even admire themselves enough to actually purchase a souvenir from the photographer.

With the city’s youth flocking to his doorstep, Sidibé cleverly capitalized on his notoriety by establishing a portrait studio in 1962; it catered specifically to the tastes of this newly defined generation. Rather than conforming to stoic portrait traditions of the past, Sidibé’s studio offered what he describes as a “laid back” environment, where his clientele didn’t feel obliged to pose stiffly in their Sunday best, but could turn up in their latest outfits (or even in their newest underwear) to be photographed with friends, instruments, watches, sunglasses, boxing gloves, Vespas, or whatever else they treasured. Even as Sidibé’s party-picture business subsided in the mid-1970s due to the rise of affordable cameras and commercial nightclubs, his studio portraits continued to flourish.

At FOAM, a selection of Sidibé’s portraits were interspersed amongst the index files, providing a fascinating alternative take on the vibrant youth culture of Bamako—one that focused on flamboyant expressions of individuality rather than the communal spirit and intimacy found at the parties. Again, although the decades are revealed through the fashions—a trench-coat “secret agent” in 1964; a sombrero and flares in 1976; a Bob Marley T-shirt in 1979; and Adidas sneakers with boom box in hand in 1986—they do not feel dated in the slightest; the fresh and playful celebration of each subject’s distinctive personality is consistent throughout Sidibé’s studio work, and remains remarkably current, despite its temporal and geographical distance. (That said, what the boy in the sea captain’s hat, Jackie O. sunglasses, studded bellbottoms, and cowboy holster with a wooden gun was thinking in 1970, we’ll never know.)

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2008. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.