Parallel Lines: ‘Street and Studio: An Urban History of Photography’

@ Tate Modern, 22 May – 31 August 2008

by Aaron Schuman

Originally published in the British Journal of Photography, 14th May 2008

In the summer of 2003, Tate Modern staged its first major exhibition of photography – ‘Cruel and Tender: The Real in the Twentieth Century Photograph’ – joining museums throughout the world in, as Nicholas Serota put it, ‘Acknowledg[ing] that photography is a key component of contemporary visual culture.’ The show sent shockwaves throughout the international photographic community, which had only recently embraced post-modern notions of appropriation and constructed narrative, by once again reemphasizing the intrinsic and tremendously complex documentary aspects of the medium rather than concentrating on the more esoteric aesthetic, theoretical or conceptual objectives of its represented practitioners (most of whom knowingly allowed the nature of the medium to guide them towards the formulation of new ideas, as opposed to simply articulating preconceived ideas through the use of photographic imagery). ‘Cruel and Tender’ celebrated photography as poignant, unifying paradox; a medium that could elegantly balance upon two sharply opposing extremes – empathetic criticism, subjective objectivity, artful record, fictions that ring true, and cruelty which remains tender.

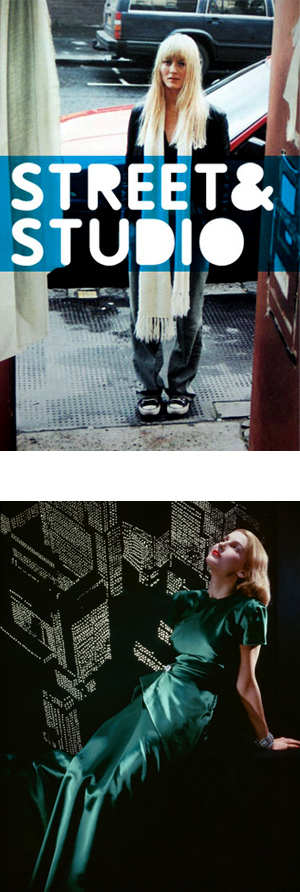

Five years on, Tate Modern is again staging an ambitious survey of more than a century and a half’s worth of photography, entitled ‘Street and Studio: An Urban History of Photography’. Yet in contrast to ‘Cruel and Tender’, ‘Street and Studio’ does not at first seem to tie together such extremes, but instead concentrates on two very different and divergent paths that photography took over the course of the last one hundred years. By focusing on site rather than sentiment, the exhibition reveals the startling impact of environment upon the photograph – as one of the exhibition’s curators, Ute Eskildsen, notes in her introductory essay, ‘Photography is exclusively tied to the places in which it is created.’

This becomes exceptionally clear throughout the exhibition’s exploration of the first half of the twentieth century, in which the work of street practitioners such as Paul Strand, Robert Frank and Lisette Model is compared with that of studio photographers such as Alvin Langdon Coburn, Cecil Beaton and Irving Penn. In these early examples of the two distinct genres, the street photographs bask in a glow of seemingly spontaneous authenticity in that they are, to borrow from Garry Winogrand, ‘figments of the real world’, whereas the studio photographs are unabashedly contrived, celebrating the photographers’ own glamorous fantasies, ornate dreams and aesthetic ideals. But what also becomes obvious is how very different the relationship between photographer and subject is within these two respective settings. On the street, despite having little influence upon the sequence of events that takes place before the camera, the photographer maintains complete control over the final representation of the subject; by simply choosing to photograph a particular person at a particularly ‘decisive’ moment, the photographer dictates the appearance, pose, facial expression, surrounding context and viewers’ perspective of the subject, without ever having to consult with the subject themselves. Therefore, the street photograph is insightful only insofar as it rather selfishly represents the photographer’s own understanding of the subject at hand – more than anything else, it is a self-portrait, and the subject is a mere prop.

Conversely, within the studio environment the photographer and subject come together in a controlled but overwhelmingly ambiguous environment, and are thus forced to confront, interact and collaborate with one another. The subject’s self-awareness and sense of participation is dramatically heightened, immediately calling the photographers’ authority into question and considerably weakening their powers of persuasion. The resulting photograph is therefore no longer a private representation of one individual’s perspective, but is instead a constructed portrait of the relationship formed between photographer and subject. As ‘Street and Studio’ progresses, what at first appeared to be a clear cut comparison of the ‘real’ versus the ‘imagined’ – the authentic experience versus the contrived encounter – soon develops into a much more complicate exploration of how, as Eskildsen describes it, ‘the street has become a site of performativity and the studio one of authenticity’.

Upon entering the latter half of the twentieth century through the exhibition, the transformation and then the gradual blurring of such boundaries becomes much more intriguing and complex. Beginning in the 1950s, street and studio photographers start to swap both locations and equipment, perhaps in a bid to benefit from the advantages of their respective counterparts, and we soon discover that such integration is continually developing to this day. Fashion photographers, who were traditionally confined within the formal studio, begin to use city backdrops and shoot ‘on location’, attempting to incorporate the apparent spontaneity of the urban landscape into their glamorized fantasies. Within his studio, Erwin Blumenfeld appropriates a stylized version of a classic New York nightscape by Berenice Abbott to emphasize the sophistication of a green silk dress; then Norman Parkinson and William Klein forsake the studio altogether and invite their models to pose on the city street itself; Helmut Newton – always one to push such contrivances to extremes – adopts the role of a voyeuristic john, shooting his haute-couture models through the windscreen with a 35mm camera as they approach his car like hookers looking for business; and finally, Juergen Teller simply snaps a picture of each model who appears at his door for a ‘go-see’, very literally looking for business.

Simultaneously, over the course of the last fifty years street photographers have adopted slower technologies, have increasingly engaged with their subjects before photographing them, have emphasized and reflected upon the self-centred nature of their work, and have occasionally stripped their images of evidence of the street entirely. Diane Arbus and Philip Lorca-Dicorcia employ artificial flash to highlight the synthetic nature of their photographic encounters; Laurie Anderson waits for men to catcall her, then turns her camera on them and asks to take their picture; Martin Parr regularly forsakes his own camera and ‘makes’ self-portraits by simply having his picture taken by the photographers and photographic studios he encounters whilst walking the streets; and Andre Serrano and Rineke Dijkstra bring studio lights, large-format cameras and occasionally studio backdrops with them, building makeshift studios on the street itself.

Ultimately, ‘Street and Studio’ presents the fascinating visual history of how two very distinct photographic approaches were born in the early twentieth century, then developed in parallel over the course of nearly fifty years, infiltrated one another, and most recently collided altogether. As the American sociologist, Saskia Sassen, has proposed, ‘Nowadays instead of public space you often have only public access’, and as notions of space converge into controlled areas of access, so too do the realms of public and private, photographer and subject, authenticity and artificiality, reality and the imaginary. After a century of to’ing and fro’ing, once again ‘street’ and ‘studio’ are one.

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2008. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.