CH-CH-CH-CH-CHANGES

by Aaron Schuman

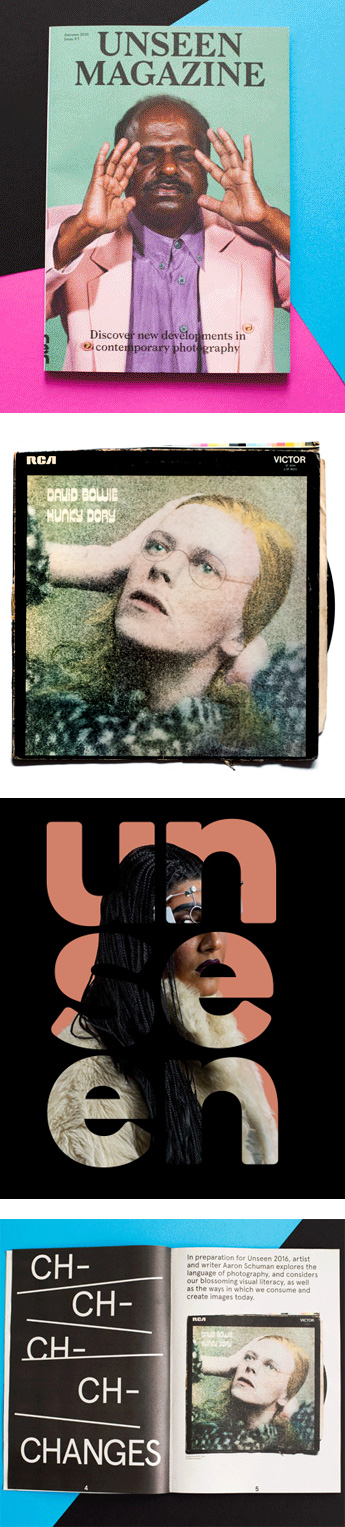

This essay was originally published in Unseen Magazine, Autumn 2016

In preparation for Unseen 2016, artist and writer Aaron Schuman explores the language of photography, and considers our blossoming visual literacy, as well as the ways in which we consume and create images today.

Earlier this week, I called into one of my local charity shops in order to drop off some old toys and clothes, and browse for books and bric-a-brac. In fact, it happened to be a Barnado’s Charity Shop, and for those familiar with particular histories of photography, the name Barnardo’s will ring with a certain significance. In 1867, Dr. Thomas John Barnardo founded the first of what were initially called “Dr. Barnardo Homes” – an organisation that established charitable institutions throughout the United Kingdom, which took in orphaned and destitute children living on the streets and housed, clothed, fed, educated and trained them for work. As part of his early campaigns to raise money for the organisation, Barnardo famously sold pamphlets and published advertisements that contained transformative “before-and-after” photographs of some of the children whom his organisation had helped. In the first of these photographs (the “before” image) the children were depicted as they had been purported to have been found on the street – filthy, barefoot, desperate, starving and dressed in rags; in the second (the “after” image) they were portrayed as clean, well dressed and healthy, often standing with the implements of a newfound trade or studying diligently at a school desk. The photographs initially sold well, and were incredibly successful in raising money and support for Barnardo’s homes. But within a few years, Barnardo was accused of staging the pictures – in some cases, even having both the before and after images taken on the same day – and taking advantage of the public’s blind faith in truthfulness and accuracy of the photographic image. In 1876, the Reverend George Reynolds claimed, “The system of taking, and making capital of, the children's photographs is not only dishonest, but has a tendency to destroy the better feelings of the children. [Barnardo] is not satisfied with taking them as they really are, but he tears their clothes, so as to make them appear worse than they really are. They are also taken in purely fictitious positions.”

Eventually, in the following year, Barnardo was taken to court over the matter. And during his hearing, although he admitted to taking some license whilst making the images, he explained in his defense that, “To illustrate [the children’s] class and their condition, we are often compelled to seize the most favorable opportunities…and the reception of some boy or girl of a less destitute class, whose expression of face, form, and general carriage may – if aided by suitable additions or subtractions of clothing, and if placed in corresponding attitudes – convey a truthful picture (because it is typical) of the class of children received.” Despite Barnardo’s insistence that, when depicting generalizations such as “class and condition”, the “typical” might be equated to the “truthful”, he was admonished by the court and, although not convicted of any legal wrongdoing, was strongly criticized for using photography to create what the court itself scathingly referred to as “artistic fictions”.

… turn and face the strange …

At the entrance of the charity shop, to the right of the front door, I noticed a blue and yellow box half-filled with LPs beside a sign that read, “Records: 49p each.” Quickly flicking through it, and not expecting to discover much apart from unwanted albums by Cliff Richard, Johnny Mathis and Barbara Streisand (which are common to such charity shop bins) I was shocked to encounter the bleached and mottled face of David Bowie on the cover of his 1971 record Hunky Dory. In the image – originally photographed by Brian Ward, and then hand-tinted by George Underwood and airbrushed by Terry Pastor – Bowie pushes back his long golden blonde hair, delicately framing his face with his hands whilst looking skyward, otherworldly and iconic. The pose is a hazily familiar one – in fact, it was inspired by a photograph that Bowie brought along to the photo shoot, of Marlene Dietrich in 1937 by Cecil Beaton, who once described Dietrich as “a sort of mechanical doll…with a genius for believing in her self-fabricated beauty” – and is striking for both its sincerity and self-consciousness, as if through the medium of photography Bowie too is both expressing and instilling a paradoxical belief in his own self-fabrication. (Furthermore, on this particular album cover, battered and fraying at the edges, Bowie’s gender bending genius was additionally complicated by the fact that the previous owner had drawn a pair of delicate spectacles around Bowie’s piercing blue eyes, and a very thin, almost prepubescent moustache across his top lip, giving him the appearance of a teenage boy with aspirations of being an aesthete or poet as much as a pop-star who’s consciously mimicking classic Hollywood glamour.) Here, the same “artistic fictions” with which Barnardo was chastised nearly a century earlier – the staged transformation of the subject, the willful manipulation of the image, the appropriation of familiar visual tropes, and so on – are precisely what gives the picture its strength and power; its blatant contradictions, contrivances, falsities and flaws are what allow it to ring true, albeit in a manner that reflects not the “typical”, but rather asks us to face different kinds of truths via the atypical, the unconventional and “the strange”.

… just gonna have to be a different man …

Looking closely at Bowie’s album cover, I was suddenly reminded of another photograph from 1996 in which the Japanese artist, Yasumasa Morimura, assumes the guise of a different but equally famous Marlene Dietrich image – adding a transracial as well as transgender spin to the original – which I first encountered in New York twenty years ago. I was in my second year of university and interning at two Soho-based galleries, Luhring Augustine and Andrea Rosen, which were both housed in 130 Prince Street, on the second and third floors respectively. Despite its limited real estate, photography, and particularly the art-based photography market, was booming at the time. During my 18-month stint as an intern I found myself installing works and posting invitations for shows featuring not only Morimura, but also Larry Clark, Wolfgang Tillmans, Richard Billingham, Gregory Crewdson, Andreas Gursky, Miguel Calderón and more.

In retrospect, it’s clear that this was a moment in which both photography and the contemporary art market were testing two ends of a particular photographic spectrum within this newfound gallery context: the apparent realism of the experiential, autobiographical and personal at one end (as conveyed in the subject matter and “snapshot” aesthetic of Clark, Tillmans and Billingham), and the hyperrealism of the staged, the performed, the constructed and the cinematic at the other (as conveyed by the heightened artificiality and blatant fabrication of Morimura, Crewdson, Gursky and Calderón). Yet what was common among all of these photographers (and gallerists) was an understanding that photography itself – at its most artistically relevant, valid and interesting – was no longer a medium of reproduction or replication, but rather one of representation, and that such representations either should explore that which was generally underrepresented in ways that were familiar and accessible, or should attempt to consciously undermine the familiarity and accessibly of photography itself through various forms of appropriation, manipulation and subversion. Within this expanding gallery context, photography suddenly became validated (and valuable) as both a medium and visual language through which we could not only encounter and experience that which had already been seen, but could also examine, express, critique and convey that which, more often than not, goes unseen.

… time may change me …

Today, whilst wandering through photo fairs such as Unseen 2016, it’s apparent that this somewhat bipolar spectrum of gallery-based photographic practice represented in the 1990s has since blurred, diversified, expanded and blossomed with a stunning sense of complexity and nuance. Of course, fascinating contemporary echoes and evolutions of these vital precedents remain: in the diaristic and seemingly casual, yet richly atmospheric and deeply personal work of Lara Gasparotto; in the vivid, technicolour imaginings – with their knowing nods to the likes of David Lynch, Alfred Hitchcock, Dennis Hopper and Russ Meyer – of Matt Henry; in the poignant interrogations of notions of identity, as defined by race and sexuality, in the portraits of Zanele Muholi; and elsewhere. But in each of these cases, the visual and photographic vocabularies with which these new artists express themselves contain a certain subtlety that relies upon a viewer that is both incredibly fluent and extremely well versed in the language of images.

It is here – in the audience – rather than in galleries, or in technological advancement, or in the practice of the medium itself, where the greatest change has occurred over the course of the last twenty years. In oversaturating us with images, providing us with an infinite and ever-growing archive of pictures at our fingertips, and compelling each and every one of us to converse, communicate and contemplate both ourselves and others through photography on a daily basis, the digital revolution has created a profoundly and intrinsically visually literate society that allows photographic artists to express themselves and explore, as well as exploit, their medium in complex, dynamic and unprecedented ways. Photography today can comfortably stretch beyond the limits of two dimensions into the sculptural and environmental, such as in the work of Navid Nuur, Amalia Pica and Rachel de Joode; it can conceptually question and disrupt the notion of the image itself whilst still remaining playful, fun and captivating, such as in the work of Tom Lovelace, Abel Minnée and Ina Jang; and it can be created and constructed for the explicit purpose of being destroyed and deconstructed, such as in the work of Maya Rochat, Alma Haser and Hiroshi Takizawa. Our photographic culture now not only accepts but also expects new vernaculars to form, new grammars to develop and new dialects to emerge within the language of photography itself – we want our visual vocabularies to grow, our photographic understandings to be challenged, and our typical “truths” to be undermined. And just as the staccato choral refrain of Bowie’s opening track on Hunky Dory repeatedly insists – mimicking the rapid fire of a camera’s shutter, or the frantic clicking of a mouse as we jump from link to link – we now embrace such “ch-ch-ch-ch-changes”, and celebrate rather than condemn the “artistic fictions” of the Unseen.

…. but I can't trace time.

Aaron

Schuman

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2016. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.