Nikolay Bakharev: Novokuznetsk

Essay by Aaron Schuman

2016

This essay was originally published in Novokuznetsk by Nikolay Bakharev (Stanley Barker, 2016)

The title of this monograph – Novokuznetsk – is simply yet deceptively derived from the name of the place in which these photographs were made; a remote Russian city of more than half a million people, located approximately two-thousand miles east of Moscow, in south-western Siberia. During Joseph Stalin’s rapid industrialization of the Soviet Union in the 1930s, Novokuznetsk was transformed into a heavily industrial center, with several major coal, iron and steel plants built and put into operation over the course of the mid-twentieth century. Today, the city remains dominated by its factories and their workforce, although under slightly less stable circumstances. It is also home to the Nikolay Bakharev (b. 1946), a mechanic turned photographer, who during Soviet times worked for the Communal Services Factory in Novokuznetsk, offering his photographic services to schools, nurseries, weddings, funerals and so on, as well as visiting parks, swimming holes, workers’ hostels and private apartments in order to produce photographic portraits for the city’s inhabitants – a career which he has retained as a freelancer to this day, long after the fall of the Iron Curtain.

In the late 1980s, Bakharev first began to receive both national and international attention for his body-of-work entitled Relationship, which consists of intensely sensitive and captivating portraits made of semi-dressed swimmers whom he approached in public, beside the nearby river. But as seen within Novokuznetsk, it is within the privacy of his subjects’ homes where Bakharev has always been most adept at stripping – both literally and metaphorically – the situation of its formality, and accessing an acute honesty and profound intimacy that is rarely captured elsewhere.

Over the course of several hours (and sometimes even over the course of several years) Bakharev manages to develop remarkably strong and trusting relationships with his subjects that, within the context of his photographic shoots, allows for a very specific form of both self-exposure and self-expression to emerge; one which often verges on notions of fantasy, but nevertheless remains firmly situated in the real, and reveals much more than the seemingly erotic first impressions that his images initially suggest. “This lady is interesting,” Bakharev remarks in a 2005 video-interview, whilst showing two photographs to the camera – one in which a slight, young woman in an oversized smock stands pensively in her bedroom, a Munch-like painting on the back wall; the other in which a dour older woman sits hunched on her bed in a t-shirt, a cigarette in hand, with similarly styled paintings in the background. “This is the same lady”, he explains, “The difference is nine years. This is her when she was seventeen or eighteen years old; and this picture was taken in 1991. After high school she decided to apply to art school. She was an artist, and that's when I first photographed her. She lived in hardship – her father was an alcoholic, and her mother…who knows what – and she wanted to be an intellectual. It never happened. Instead of art school she ended up at the plant. After nine years had past, I came to her apartment again. She trusted me because we had something before. But after nine years her situation remained the same.” With a hint of sadness as well as poetic resignation, he later reflects, “Nothing changes in their world, no matter how many years pass by. Things never change."

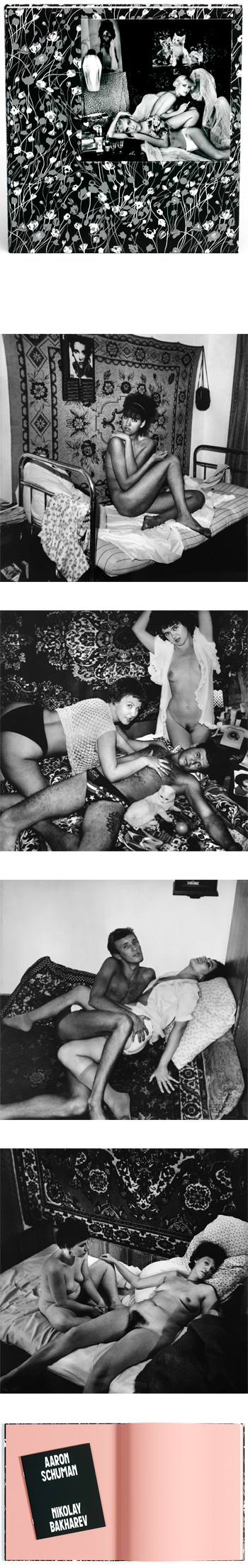

On their surface, neither of the fully-clothed photographs described above are entirely characteristic of Bakharev’s “interior” or “private” portraits (and in fact, they do not appear in this publication), but they do reveal the importance that Bakharev places on his relationships with his subjects, as well as emphasize the important underlying duality that exists in his work – between desire and sincerity, between fantasy and reality. That said, more often than not, over the course of an extended session Bakharev’s photographic subjects are gradually encouraged to remove their clothes, and pose semi-nude or entirely naked before his camera. Boldly but nevertheless self-consciously posing within the frame – either alone, in couples or in threesomes – they begin to writhe and contort, spread open and entwine, lounge across and twist around one another, gently embrace and, in some instances, go so far as to pleasure themselves or each other.

It would be easy to misinterpret these images as simply the pornographic imaginings of a manipulative and dirty old man, yet there is something else within them – in the subjects’ eyes, in their frankness, in their curiosity and collusion, as well as in their surroundings – that suggests that much more is going on here, and that what is both at stake and in evidence stretches far beyond the realms of explicit sexuality, voyeurism and mere titillation. As the revered photographer, Lee Friedlander – who himself spent many years, from the late 1970s onwards, photographing Nudes in the tapestry-draped living rooms and throw-strewn bedrooms of his own models – once ruminated: “It's a generous medium, photography." At the time, Friedlander was more generally referring to the overwhelming amount of information that a picture can contain, and the plethora of details that can be captured within a split-second, sometimes unbeknownst to the photographer himself: “I might get what I hoped for and then some – lots of then some”, he stated. Like Friedlander, Bakharev is not afraid to fill his frame with “lots of then some”; to overwhelm the viewer with the richness of what lies before him frozen in time. Beyond the naked bodies, his photographs are wondrously crammed, cluttered and overflowing with many more intriguing details than what initially appears to be the primary focus of his attention. The bare figures at hand are surrounded by an environment littered with the objects and ephemera of everyday life: rugs and bedspreads, coffee mugs and cigarette smoke, alarm clocks, magazines, radios and televisions, posters of kittens and puppies, and pictures of adorable babies, supermodels, Vladimir Lenin, Ernest Hemingway, and The Rolling Stones. In these details, we are reminded of the ordinariness of the context in which these photographs are being performed, as well as of the more general time and place within which they occur – a far-flung part of Russia, both immediately before and after the collapse of the Soviet Union, in which cultural influences, values and aspirations are flooding in from the West, and being experimented with and adopted in unexpected, and often awkwardly uncomfortable, ways.

One off the most loaded and “generous” of Bakharev's images is that of a libertine trinity. A man, darkly tanned, lies languidly across a bed, surrounded not only by the dizzyingly-patterned oriental rugs that cover almost every surface, but also by two members (perhaps three, if one counts the small white cat lying beneath him) of the fantastical harem that they seemingly imply. Two women hover above him – one nude, apart from a frilly, wide-open silken negligee, who poses with her arms raised and her head cocked coquettishly to the side in classic pin-up fashion; the other, still in her underwear, crawls over him, her hand outstretched and gently clawing at his chest (the gesture mirroring that of the cat that lies below them, who paws at a small ball). At first glance, there is certainly something salacious about the picture, at least in what it appears to mimic and intend. These costumes, gestures, and the scenario itself are very familiar, and borrow from centuries of erotic visual tropes (such as countless classical depictions of The Three Graces or The Judgement of Paris, or the French Orientalist paintings of the nineteenth century) as well as from more contemporary pornography. The casting and styling in itself brings several obvious visual references to mind – the standing woman appears to have stepped out of a 1920s Man Ray (i.e. Kiki de Montparnasse) or Brassaï (i.e. Paris by Night), whilst the other recalls the pulp-fiction covers and sexploitation films of the 1960s, or even more amateurish, “Readers’ Wives”-like erotica that surfaced around the same time. Furthermore, the man – with his bronzed body and thatch of chest-hair – seems to have walked straight out of central casting for 1970s American porn films, complete with tight-fitting underwear that bear a stars-and-stripes design, and a logo that boldly reads, “USA”.

And yet, the surrounding details reveal notions of pretense and mimicry, as well as a more down-to-earth realism and ordinariness within the scene, in many ways betraying the attempted fantasy and its construct. A 1993 issue of the French pornographic magazine, Cheri – with the porn-star Serenna Lee posing as Marilyn Monroe on its cover – creeps into the bottom of the frame, whilst a rolled up copy of Cosmopolitan peeks out of the center-right of the image, propping up the man’s head. Various toiletries, a rotary telephone, a newspaper and magazine clippings litter a nearby bedside table. And most strikingly, the subjects’ themselves stare out of the picture, calmly yet directly at the photographer – and the viewer – almost quizzically, as if asking, “Is this what you want?”…or perhaps even, “Is this what we want?” As Bakharev himself explains, by “exploiting the stereotypes of beauty that float in the minds of people” the dreams and desires of his subjects “suddenly turn into frankness, when tested with reality.”

In the past, much has been made of Bakharev’s precarious underground status during Soviet rule, when a clause in the official Criminal Code specifically forbade both the making and distribution of images containing nudity, and he therefore had to make such pictures in secret and for himself and his clients (the subjects themselves) only, whilst constantly under threat of being incriminated as a pornographer by the KGB – what Bakharev has referred to as his “operational costs” during that period. Several of the photographs included in Novokuznetsk were certainly made within this period – in the mid- to late-1980s – yet with the impending decline and then the fall of the USSR came promise of freedom, independence, open-mindedness and opportunity within Russia, as well as the influx of Western media, morals and aspirations within even the most remote reaches of Russian culture. In turn, during this period both a longing and lust for life arose within society, and it is precisely here – where lust and longing collide – that Bakharev’s photographs are ultimately situated. "I am working with social themes,” he explains. “Artists speak of spiritual content – they look for the spiritual content…[but] I don't use such words; I speak of interesting relationships.” As in the photograph described above, Bakharev’s interest does not so much lie in creating entirely convincing fantasies – sexual, spiritual or otherwise – but rather in documenting what happens when people are given the freedom to fantasize, and exploring the implications and uncertainty of this when it occurs within the context of a rather stark reality. “You will see the culture and the time through them” he states in a 2005 interview, “The culture and the time is what will remain…And as for beauty…it does not exist…Relationships exist, so pure and open. And not only relationships between [the subjects] themselves – they are related to us too.”

In a sense, although on their surface they are often kitschy, crass and playful, with cute kitties and dated bohemian or youth-culture references scattered alongside overtly-staged sexual performance, there is a profound seriousness and depth to what are ultimately profoundly empathetic documentary portraits, not necessarily of individuals but more specifically of relationships. In contrast to the image of the wanton threesome described above, another of Bakharev’s photographs – set on another bed, in front of a similarly ornate, carpeted backdrop – captures two more heavyset women in the nude, one of whom sits comfortably looking calmly at her companion, whilst the other lies back, relaxed, as if floating, and rests her head on a pillow and her hand on her partner’s knee, staring openly at the camera. Like the two subjects, the photograph is quiet, reflective, serene and without explicit sexual charge in a way that, amongst all of the other pictures, hints at Bakharev’s truest intentions. It is a portrait of two people, and at the same time a document of the intimacy of a connection – between sisters, friends, lovers, we’ll never know – which both moves and confuses the viewer, the nudity itself acting as a symbol of ultimate trust and privacy within the relationship (on the part of the subjects), as well as a catalyst for the uncomfortable, voyeuristic disruption of that relationship (on the part of both the viewer and the photographer). But as Bakharev once explained to several of his subjects – and more indirectly yet poignantly to his audience – during one photographic session, whilst he directed them to twist and contort before his lens: “You know that you live in the four dimensional world – you've had it in school; length, width, height and time. But I only have two dimensions in photography. So to squeeze you into two dimensions, I have to make you uncomfortable sometimes.”

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2016. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.