'In Appropriation' presented a selection of contemporary photographers who directly instigate strikingly new photographic work through the appropriation of pre-existing imagery – whether it be found, historical, canonical, personal, archival or otherwise.

'

Appropriation' has been an important conceptual strategy within the visual arts for nearly a century. But in the case of the artists presented here, this act is not purely a matter of taking an image from one context – be it history, advertising, or the vernacular – and placing it within another: that of the gallery, the museum, 'fine art'. Instead, these photographers are carefully examining, incorporating, and then transforming – or riffing off of – such pictures in an effective, engaging, and incredibly original manner.

Within the digital age, photography's past and present (and in a sense, its future) have collapsed and merged, and at the same time have been revealed to be seemingly infinite and ever-growing. This exhibition represents a new generation of practitioners who are harnessing the power of this collective mass of imagery, and are using it to instigate and inspire brave new forms of critical inquiry, creative experimentation, political engagement and personal expression.

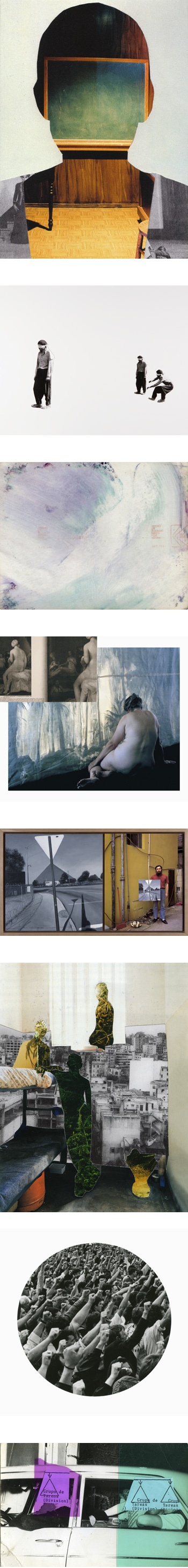

AFTERLIFE

by Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin

2009

The "Afterlife" series offers a re-reading of a controversial photograph taken in Iran on 6 August 1979. This remarkable image, taken just months after the revolution, records the execution of eleven blindfolded Kurdish prisoners by firing squad. The image, which captures the decisive moment when the guns were fired, was immediately reproduced in newspapers and magazines across the world. The following year it was awarded a Pulitzer Prize, and for the next thirty years its author was simply known as "Anonymous." Only recently has the photographer's identity been revealed as Jahangir Razmi, a commercial studio photographer working in the suburbs of Tehran. He was located and interviewed by Joshua Prager of the Wall Street Journal.

Broomberg & Chanarin sought out Razmi, and based on their discussions, along with an examination of the neglected images on the roll of film Razmi produced that day, they present a series of collages – an iconoclastic breakdown or dissection of the original image – that interrupts our relationship as spectators to images of distant suffering.

PEOPLE IN TROUBLE LAUGHING PUSHED TO THE GROUND (DOTS)

by Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin

2010

People in trouble laughing pushed to the ground. Soldiers leaning, pointing, reaching. Woman sweeping. Balloons escaping. Coffin descending. Boys standing. Grieving. Chair balancing. Children smoking. Embracing. Creatures barking. Cars burning. Helicopters hovering. Faces. Human figures. Shapes. Birds. Structures left standing and falling...

The Belfast Exposed Archive occupies a small room on the first floor at 23 Donegal Street, Belfast, and contains over 14,000 black-and-white contact sheets, documenting the Troubles in Northern Ireland. These are photographs taken by professional photo- journalists and 'civilian' photographers, chronicling protests, funerals and acts of terrorism, as well as the more ordinary stuff of life: drinking tea; kissing girls; watching trains.

Belfast Exposed was founded in 1983 as a response to concern over the careful control of images depicting British military activity during the Troubles. Whenever an image in this archive was chosen, approved or selected, a blue, red or yellow dot was placed on the surface of the contact sheet as a marker. The position of the dots provided Broomberg & Chanarin with a code, a set of instructions for how to frame these photographs. Each of the circular photographs shown reveals the area beneath these circular stickers, the part of each image that has been obscured from view since the moment it was selected. Each of these fragments – composed by the random gesture of the archivist – offers up a self-contained universe all of its own; a small moment of desire or frustration or thwarted communication that is re-animated here, after many years in darkness.

MYTHOLOGIES

by Esther Teichmann

2010-2012

Esther Teichmann's artistic practice spans across the still and moving image, collage and painting; she creates alternate worlds, which blur autobiography and fiction. Central to her art lies an exploration of the origins of fantasy and desire, and how these are bound to experiences of loss and representation. Working with intimate subjects, turned away bodies, and mythical landscapes, her works deal with the relationships between images, and the narratives such juxtapositions create. Ideas of an impossible return, of grief, and of a sense of inherited homesickness are repeatedly returned to within primordial spaces of enchantment.

"Teichmann's utopian island-world lies somewhere between black and blue seas, between here and now and the fantasy of where one might go, or perhaps, even, where one has been." (Carol Mavor)

THE PHOTOGRAPH AS CONTEMPORARY ART

by Melinda Gibson

2009-2011

Melinda Gibson's series, "The Photograph as Contemporary Art", examines the seminal educational text of the same name by Charlotte Cotton, first published in 2004 and re-published in 2009. Through the medium of photomontage, each of Gibson's pieces is a trio of imagery that has been removed from the book and re-contextualized as one work. This body of work brings forth questions surrounding our educational system, copyright, and licensing, as well as audience participation.

As the publication of imagery continues digitally, every image can be searched for, clicked on, cut, copy, pasted. Yet a book manages to hold onto its copyright, as by law you may only reproduce 10% of the entire volume. What becomes apparent is the canonization of imagery found in such sources – the same photographers, images appear and re-appear. This sameness is only reiterated through the educational system bound to our institutions. These textbooks that are presented to us, to hold dear, do little to expel such problems. Or do they?

Taking such texts apart helps to really question this canonization, far more than when they are considered within the constraints of a book. By slicing, cutting, and composing these images against one another, they are decontextualized, and recreates into new dismembered realities.

Each work in "The Photograph as Contemporary Art" is composed of three separate parts, where the same sized images are manipulated into one; placed under or over one another, parts have been removed and discarded, while others have been added. Each image is an appropriation of an original, re-organized with additional elements that makes itself into a new original. Through such deconstruction one starts to gain a greater appreciation of the works, and starts to understand why and how these photographers, and these images, have become so prominent.

UNCLASSIFIED (76-83)

by Seba Kurtis

2010

"The United States government recently approved the release of classified files relating to the last dictatorship in Argentina (1979 - 1983). These secret documents reveal detailed evidence of the massive atrocities committed by the Argentinian military more than thirty years ago. It also includes a transcript of Henry Kissinger's staff meeting, during which he ordered immediate U.S. support for the new military regime.

This artwork was born out of my frustration - with the deception of the U.S. government, who withheld files that prevented the conviction of mass murderers, and with the practical irrelevance of the recent release of the files."

- Seba Kurtis, April 2011

SHOEBOX

by Seba Kurtis

2010

"I was gutted when they took our T.V. I was a teenager at the time, and I remember that I was alone in the house with my mother that day. I saw her crying. She was signing some paper, and I asked her what was going on. She replied, 'None of this stuff belongs to us anymore.' After being repossessed, we were left with only our clothes and a shoe box full of photos. It was difficult for me to understand at this point as I wasn't interested in economy or politics; all I knew was that my dad lost the business, we lost our home, and we had to start again from scratch. My dad and I were up for anything, from selling vegetables at the market to selling newspapers at traffic lights.

The Argentinean "middle class dream" was over for many families at that moment. When the next crisis hit, I was in my twenties and I fully understood the situation. You could blame political corruption, multinationals, globalisation, or the sacrifice of Latin America. But at the end of the day, when you struggle to put food on the table for your family, you feel that you have failed as an individual. And that is the look that I saw on my father's face.

So after that, being an illegal immigrant was no big deal for me or my family. We saw it as a positive opportunity for us to move forward and make a new start in Europe.

I started to work in a construction site in Spain, with people coming from South America and Africa. The first to join me was my sister. The Argentinean government then made a pact with the international banks, and froze everybody's savings for a year. Next my father came. He worked nights as a security guard, and within six months we had saved enough money up to send for my mother and youngest brother to join us. She worked long hours as a chambermaid in hotels. Sometimes they withheld her wages.

After many years, we all got permission to stay in Europe. Two years ago my parents returned to Argentina, and came back with a treasured old shoebox of family photographs that had been left at my grandma's house. They had been damaged by a flood.

I decided to include some of the backs of the photographs. They were stuck to each other. I was attracted to them - the traces of other pictures, emulsion, colors. Photos that we never will see again, but have left a mark.

Shoebox is my family history. Hope."

- Seba Kurtis, 2010

REAL FAKE ART

by Michael Wolf

2011

In front of typical Chinese urban backdrops young Chinese men and women present oil paintings by American and European artists from different epochs. Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha, even photographs by Lee Friedlander, William Eggleston, Bernd and Hilla Becher or August Sander can be found among the works. What stands behind all this?

In fact we see pictures of a multi-million dollar industry – the production of copies of popular artworks, which are sold at giveaway prices into the whole world. Van Gogh: $75, Andy Warhol: $28, Ed Ruscha $50. The handpainted copies mainly come from China, but the buyers can almost entirely be found in the United States and Europe, the countries of origin of the unaffordable originals.

Michael Wolf has photographed the Chinese copy-artists, and in his photographs he has placed manifold relations between the picture subject, the urban environment, and the portrayed artists, which reaches far beyond the superficial humor of the images.

''In Appropriation: Broomberg & Chanarin, Melinda Gibson, Seba Kurtis, Esther Teichmann, Michael Wolf" (Curated by Aaron Schuman)

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2012. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.