Foreword: The Photograph as Contemporary Art, by Melinda Gibson

by Aaron Schuman

September 2012

This essay was originally published inThe Photograph as Contemporary Art, by Melinda Gibson.

In a 1908 essay entitled 'Is Photography a New Art' – published anonymously in issue twenty-three of Camera Work, but suspected to have been written by Alfred Steiglitz, the journal's publisher and the foremost champion of photography as 'Art' at the time – the author states:

'Man cannot truly create; but he can stick things together in such a way as to illude into the belief that he has created; and it is this esthetic quality of composition which all the fine arts must possess.'

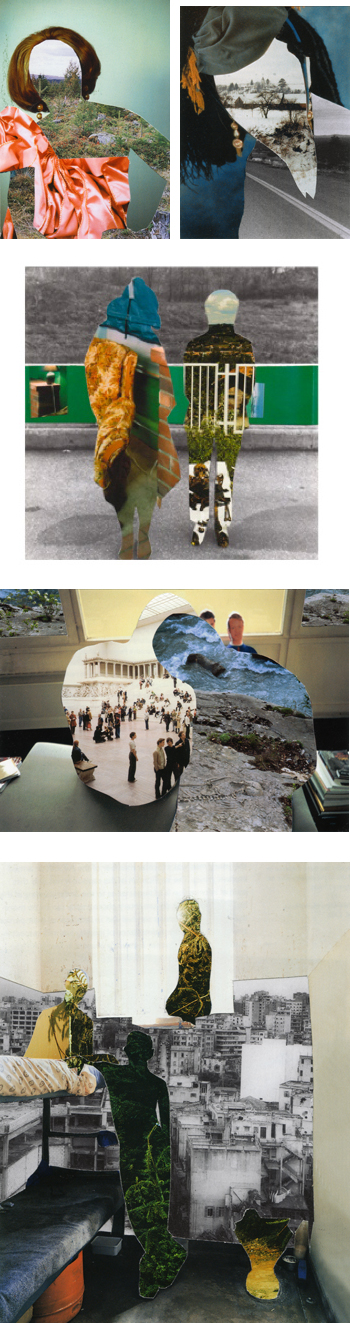

Melinda Gibson's series 'The Photograph as Contemporary Art' adheres to this theory, quite literally. She 'sticks things together' – in this case, sliced-up images culled directly from the pages of Charlotte Cotton's seminal book, The Photograph as Contemporary Art, which has graced the reading lists of nearly every academic institution offering a degree in photography since its publication in 2004. The resulting collages are both playful and haunting, metamorphosizing the photographs that originally accompanied Cotton's text into 'compositions' – into creative illusions – that are entirely her own. For any photography student (or for that matter, photography teacher) of the last decade, Gibson's works conflate hours spent in darkened lecture theatres, brimming photo bookshops and gleaming-white galleries into singular experience; they transform years of diligent and directed image absorption into a psychedelic trip down memory lane, as if a Gibson herself, posing as a photographer, had managed to capture stills from a dream the night before a big exam.

Beaumont Newhall – regarded as the godfather of photo-historians, whose seminal work also eventually went under the knife, both critically and physically (most notably in George Blakely's massive, tapestretic collage, Beaumont Newhall – The History of Photography (1987), which serves as eerie precedent to Gibson's work) – once reminisced, 'I wanted to borrow a photograph [from Steiglitz] for the Museum of Modern Art. He said the photograph would be released if I would insure it for five-thousand dollars. The Museum took a deep breath at this, and the insurance people had to be persuaded, and I finally went over with the policy of five-thousand dollars in my hand. [Steiglitz] then gave me the photograph, tore the policy in two, and said, "I just wanted to teach you to respect the photograph."'

In a sense, by tearing into the photographs published in The Photograph as Contemporary Art, Gibson also tears into the 'insurance policy' provided by Cotton's book for the images, and artists, that appeared in its pages. It's important to note that the Cotton introduced her text by asserting, 'The aim of this book is not to create a checklist of all of the photographers who merit a mention in a discussion on contemporary art' , and many of the artists included in it were not yet part of any particular canon, but were instead rather unexpected, unconventional, or little-known at the time. That said, despite Cotton's best intensions and because of both its incredible popularity and the academic authority it quickly gained, The Photograph as Contemporary Art has – amongst other things – ultimately served to canonize many of the images and artists included within it for an entire generation of photographers. As Gibson pointed out on her blog when she first initiated this project in 2009, 'The importance of canonisation within the education system becomes apparent as the same names, images dominant our institutions. For me, taking this book apart helps to question these images, far more than when they are within the constraints of a book.'

Yet paradoxically, Gibson concluded the same post by stating, 'By slicing, cutting and de-contextualising the images I start to gain a greater appreciation of the works; I start understanding why and how the these images have been created.' Having liberated these photographs from the conceptual and commercial confines of 'Contemporary Art' – the context within which they were admittedly born, flourished, and in many cases, for which they were precisely intended – and by melding, merging, and re-engaging with them in her own unique way, Gibson allows them to cross a particularly poignant threshold, into a more unmitigated and arguably more suitable realm: that of Photography itself.

In a 2011 interview, Cotton herself remarked, 'I could only write [The Photograph as Contemporary Art ] now if "Contemporary Art" was understood as a museological term for a period in art-making that, for most museums, started around 1965 and ended around 2010...I think that the very nature of the time that we're now living through has led me to change my opinion about lots of things profoundly. And to not change your opinion about something that is shifting so radically is to not be really and truly invested in it.' Since Photography's invention, its relationship with Art, contemporary or otherwise, has proved to be both passionate and productive, but also incredibly tumultuous, at times quite dysfunctional, and most recently, strikingly co-dependent. Yet as Cotton points out, perhaps another change of heart is in the air; and thankfully, throughout all of the ups and downs, the medium has admirably managed to maintain its integrity, its intensity, and its vital independence. To return to the prescient anonymous essay that appeared in Camera Work more than a century ago, 'The conclusion, then, that we have come to is, that photography is one of the fine arts, but no more allied to painting than to architecture, and quite as independent…as any of the other arts…Photography is photography, neither more nor less.'

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2012. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.