EURASIA: In Conversation with Taiyo Onorato & Nico Krebs

This interview was originally published by Fotomuseum Winterthur, Eurasia (Exhibition Catalogue), 2015 - http://www.fotomuseum.ch/

AS: Aaron Schuman

TO: Taiyo Onorato

NK: Nico Krebs

AS: Firstly, how did the project, Eurasia, begin – what inspired you to go east?

TO: Several years ago we did The Great Unreal, a project which centred on road-trips we took through the United States between 2005-2009. After that, we stayed closer to home for a while – mostly in Berlin – doing various still-life projects and working around the city. Then, in 2013, we felt like it was time to go on another long trip, but this time to head in the opposite direction.

NK: We were curious about what it would be like to drive for thousands of kilometres in one direction. We sensed that it would be challenging, and maybe more fulfilling than flying from A to B, and just looking down from above.

TO: Our first eastern-bound trip took four months, and the biggest challenge was simply to get all the way to Mongolia. It was about moving forward, getting the right visas, overcoming problems with the car. And during this time we worked in a “documentary” style – really, we were just wandering around, collecting images, and trying to gain more understanding.

In a sense, we’re very lucky in photography today, because we can quote so many things. Depending on how you photograph, and what materials and technologies you use, you can quote other photographers or other photographic genres and cultures – you can make it “American-Landscape”, or “Japanese-Street”, or “Contemporary-Conceptual”. There are so many photographic keys and languages, and part of the challenge today is to play with those.

But Eurasia as a region is very challenging in this regard, because it’s completely the opposite from the United States. In the States, there’s so much imagery and iconography to play with and play off of, but Eurasia doesn't really have familiar iconography or an established visual language within our culture. In terms of imagery and references, the East was more like a black hole for us, so we had to take an entirely different approach.

AS: How many trips did you take during this project?

TO: In 2013, we took the first trip together, driving from Switzerland to Mongolia. We returned to Mongolia together in 2014, and made two more trips individually. After a few months, you start to feel like you want to stop gathering material, start analyzing it, and then go back later and create more.

NK: Four months on the road is a long and intensive experience, and sometimes its good to rest for a little while – wash your clothes, shave, sleep in a proper bed, and so on.

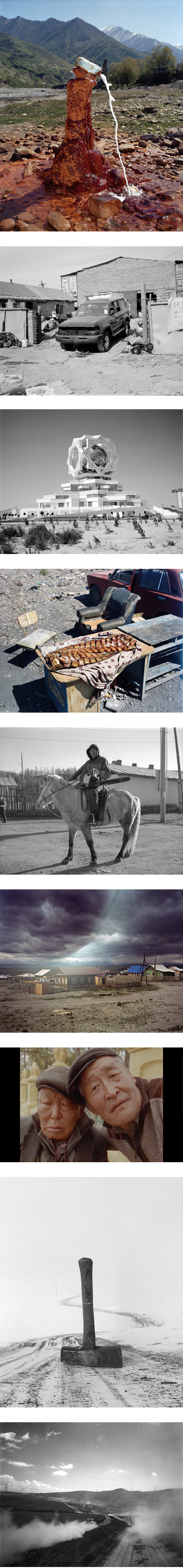

AS: There’s an interesting contrast between the past and the present, and maybe the future, in Eurasia. Many of the photographs seem specifically focused on recently built environments – new buildings, new roads, new infrastructures and monuments, and so on – as well as on older, more traditional objects and structures. Did you feel as though you were, in some sense, traveling through time as well as space?

NK: As soon as we left the “West“, so to speak - lets say, east of Vienna – we started to notice that everything was in an extreme state of flux. Many of the former Soviet republics are in a period of rapid transition, and there’s a different pace, as well as an enormous will to go forward. This is especially true in urban environments – with new roads, architecture, and mostly consumer-oriented infrastructures – whereas many of the rural regions remain static, or are even going backwards. The shift becomes surreal, and increasingly difficult to process. In some places you can travel just fifteen minutes and go from seeing shepherds on horseback living in tents, to Prada shops and Porsche SVUs.

TO: This project is a lot about time. In Mongolia, if you stay on the new roads, its similar to a Western experience – the streets, gas stations seem pretty familiar. But as soon as you drive on the back roads, it feels as though for every hundred kilometres you travel, you go back a decade in time. I like to look at an image and not be able to tell what time it’s from, and I like the thought that, as you gradually leave Europe, you go farther and farther back into time.

NK: And then all of a sudden, half-way across, you encounter the future. New mega-cities are being built in the middle of the desert, full of surveillance cameras and irrigation systems.

TO: Cities like Baku, in Azerbaijan, or Astana, in Kazakhstan, are trying to build symbols like the Sydney Opera House and the Eiffel Tower. They want to define their identity very quickly, and are really outspoken and free about this. In Europe, such epic undertakings require a long process, with years of discussion before something ever happens. But there, they just build it. This mix of turbo-capitalism, a craving for identity, and the need to make a statement is very interesting.

AS: In some ways, Eurasia is a very loose, “documentary” project about this region, but it also seems to represent the experiences and ideas of traveling itself, and the feeling of passing quickly through very foreign and unfamiliar places. There’s a sense that you’re constantly on the move, gathering quick glimpses and interesting insights, but not necessarily gaining an in-depth understanding.

TO: That’s true. The thing about a trip like this is that you’re always just scratching the surface – or driving across the surface – and the landscape around you constantly changes. It remains a very personal look at things, and what I like about working with imagery is that you can tell the truth with it, but you can also lie with it, and mix everything together. It’s always your own construction.

In Eurasia, I was really impressed by how the people use things and then recycle them, find other uses for them, and give them a second life. For example, tires: after they’re used to travel on the roads, they’re then put to other purposes – they’re used to isolate pipes, or made into door hinges, or flower planters at gas stations. This was fascinating to see.

AS: During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, it was assumed that if Western photographers or ethnographers went into regions such as these, it was their role to both capture and present an authoritative – and in a sense, a “true” or “complete”– description of the place. But within your work, you seem very comfortable with things being incomplete. Even technically, the work itself has a kind of raw quality; there are “flaws” and “mistakes” – in terms of the prints, exposures, and so on – which you seem to embrace.

NK: The artistic imagination can, and should, allow itself to be selective and incomplete – otherwise we’d be scientists, and would be forced to sacrifice our individual perspective for the sake of objectivity. It’s a freedom that we should be aware of, and should use to our advantage. Besides that, I believe that most of what’s regarded as “authoritative“ or “complete“ is really a farce. Our world is far too complex and infinitely interesting to ever claim a holistic understanding of it.

TO: And losing control is really helpful. I’m very skeptical about keeping everything under control. It’s like driving into unknown territory – you could take the left road or the right road, and if you take the left one you’ll see fascinating things, but you won’t see what lies along the other one; you always miss something. So I feel more comfortable in not making everything seemingly complete or definitive; I think it’s more honest that way.

NK: It’s also fun to imagine all of the things that you missed along the other road. For too long, photography has sat in the “objective” drawer; people should get used to the idea that it has a place in many other drawers too.

AS: On your initial journey together in 2013, did you use maps, or did you just aim the front of the car east every day?

NK: We had a rough idea of which way we would drive, but we made many detours along the way. We could have taken a more direct route, but we wanted to avoid the rather monotone landscapes. To navigate, we had foldable maps, as well as a GPS with digital versions of old Russian military maps, which turned out to be very useful. That said, in a country like Mongolia you have to navigate more by people’s descriptions and your own gut feeling, since the dirt roads are also nomadic. But this is rapidly changing – a new network of tarmac roads is being built as we speak.

TO: Driving eastwards was a very nice feeling, and after two months of traveling it really felt that we were constantly going in the same direction. Once, in Kazakhstan, we had to drive two-hundred kilometers west in order to get over a mountain pass, and it felt completely weird, as if we were going in the wrong direction.

AS: As we discussed earlier, much of the photographic work in Eurasia focuses on architecture, the built environment, and the material world, yet the films centre more on people, portraiture, human relationships and human interactions.

TO: It’s funny you mention this. In the past, we never really photographed people; I always had mixed feeling about the portrait, because it’s always just a very limited glimpse or interpretation of the real person. But when we started filming, the first thing we aimed the camera at were people. I don't know why – it was probably because when you film somebody for fifteen or twenty seconds, you already have so much more information than in a photograph, and get so many more impressions.

NK: Maybe in the past we couldn't handle the stillness of the portrait – there had to be a movement with it, even if it was only the nostrils flaring or the eyes blinking. Movement is the proof that these people exist, and breath. We needed twenty-four frames per second to approach our own species.

AS: I also noticed that many of the films center on groups of men, and on very physical, collective male activity. Do you think that this is something that is particularly representative of the region, or is it more representative of your own interests?

NK: With the two of us being a small “group“ of men, we naturally attracted other groups of men.

Usually they just wanted to chat with us, and maybe have a look at our car’s engine.

TO: We tried to film women as well, but in some countries it turned out to be very difficult – the women wouldn't agree to be filmed by themselves, and would call their husbands or fathers to ask if it was okay. It was a bit complicated.

NK: In most of the regions we visited, men stood in the foreground while women remained in the background, which is actually pretty typical – not only in central Asia, but in most parts of the world.

TO: In terms of collective male activity, we were particularly interested in two events, both of which blur the boundaries between play and violence. Firstly, Mongolian wrestling, which is very important to Mongolian culture and identity, and represents an important part of their ancient traditions. Alongside horse-riding and Genghis Khan, wrestling is often referred to as one of the pillars of Mongol society.

NK: And then we also filmed the “Lelo” – a traditional event of unclear origin, which happens every Easter Sunday in Shukhuti, a small Georgian village. Each year, they stitch up a big leather ball, fill it with soil and wine, have it blessed by the local priest, and then hundreds of the village men –who are divided into two teams – jump on it, and try to bring it into their turf. It’s a very confusing and ritualistic sight; both teams play in honour of a recently deceased person, so it’s about honour, ancestors, and manhood. The teams work out their strategies for months, and then there’s this one weekend when everybody gets horribly drunk, they play the game, and then continue to talk it over for months afterwards.

Earlier you asked about how we deal with incompleteness – or a lack of in-depth understanding – while we’re travelling. That’s partly what this work is about. In the film, you never see the ball, and as an onlooker, you can’t figure out what’s going on. The whole thing looks much more aggressive and dangerous than it actually is.

AS: In the film of the Mongolian men wrestling, I noticed that you captured their initial face-off and embrace, but mostly cut away before either wrestler became dominant. In a way, it also seemed like a self-portrait – of the two of you – in terms of working together, and producing this project.

TO: Yes, it’s true – a constant struggle of sorts. But when we were filming the wrestlers, what I saw were young men giving their best; trying to win the situation over in the foreground, with a new and rapidly expanding city in the background. For me, it’s a strong image. Within the Mongolian population, there’s a tiny minority that is very rich, but the rest of the people hardly have anything at all. At the same time, they’re building this huge city, Ulaanbaatar, and I had the feeling that a lot of people were struggling within it. They’re giving up their nomadic life, moving to the city, and their values are changing. Yet, many things still remain the same. The suburbs are made up of Gers (or Yurts) instead of houses, and every Mongolian boy still learns to wrestle when he’s four years old.

AS: How does the collaboration between the two of you function?

TO: We’ve been working together for more than ten years. In the beginning, we were working very closely – everything was basically made together – but recently, this has begun to change. In the last few years, we’ve tried to open it up a bit, so that we have space to work by ourselves. That said, it still all flows into the same pot.

AS: Surely there must be instances of disagreement or conflict – maybe times when one of you makes something, but the other person doesn’t feel that it should go into “the pot”?

NK: It would be odd if we were to say that there were never any conflicts. We’re two individuals, with two different opinions, so of course there are going to disagreements.

TO: And sometimes what happens – which is even more difficult to resolve – is that you make something that you yourself don’t find particularly interesting, but the other person thinks it’s really good. There’s a constant discussion about the images, what they communicate, and how to put them together, and this is something that I really like about working in a duo. For me, making this work is a lot about communicating, and in a duo you can discuss and test it to see if its working; if it’s communicating, or not. That's immediately the first step.

AS: So now, when you’re working independently, are you making work for each other first and foremost?

TO: To be honest, when I photograph I don’t really think a lot. We still work in analogue formats and this is one of the nice things about working in this way – I just see something, I push the button, and then think about it much later.

AS: Why do you only work in analogue formats?

TO: There’s a nice quote from a manifesto by the musician, John Cage: “Don’t try to create and analyze at the same time.” For me, analogue mediums really help me to work like this, because there’s a distance between the creation and the analysis of the material. This is true photographically, but also in terms of our films. We use 16mm, and it’s great because during the day I can film something, and then in the evening I can’t look at the footage. I simply don’t have the option. So instead, I just think about it – I think about what I’ve done, imagine how it might look, consider what I could do better – and this gives me a lot a freedom. It slows down the process.

NK: At the same time, it’s also an enormous restriction. Because we work with physical material, its physically limited. Digital media gives you a false sense of infiniteness – the only limitations are battery life and the size of your memory card. But when you shoot 16mm, you have to deal with running out of film, and the sad fact that every minute costs a small fortune. It probably heightens our awareness and concentration while working, in the best cases at least.

TO: And photographically, there’s another aspect of the analogue process that’s very important to us. Because we print the black-and-white work ourselves, in the darkroom, we end up spending a lot of time with our photographs, and get to know the work intimately. The slowness of the process creates a more thorough relationship with the work itself.

AS: I would imagine that, when you first returned from these trips, your memories were still very fresh, but that over time the photographs and films began to overtake and perhaps replace certain memories, whilst other memories faded.

NK: There’s always this period of transition. Many memories fade away, and it’s mostly the ones connected to the pictures that remain strong. I think our work needs this time, so that we can fully process what we’ve seen.

TO: And of course, if someone comes to see our show, they don’t have any of our memories – their experience is based purely on the works that they can see in the gallery. When I start to forget, that’s when the project starts to become about the photographs, the films, how we edit them and put them all together. I become more like the viewer than the author – and this is good. Forgetting all of these memories - the side-stories and things that happened day-by-day – is a kind of liberation, for both me and for the work itself.

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2015. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.