Photograms of Wildcats and Screengrabs of Strippers

by Aaron Schuman

Spring 2013

This essay was originally published in CPhoto: Observed, Edited by J. Colberg (Madrid: Ivory Press, 2013)

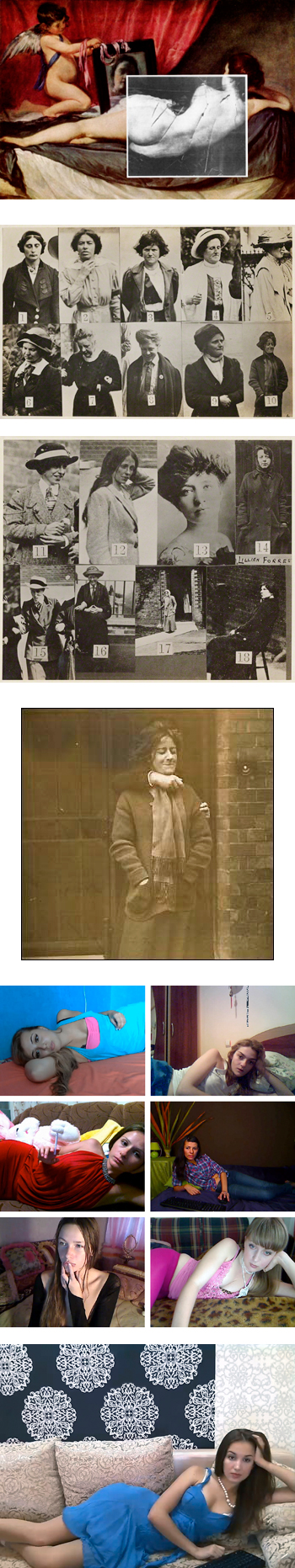

In the spring of 1914, museums and galleries across London acquired photographs of eighteen women. All of the original silver bromide prints had been numbered, and then mounted in a grid-like pattern onto one of two sheets, which were then re-photographed and reprinted. In terms of contemporary art practice, such techniques seem entirely valid, but at the time these images were not collected because they were in any way considered works of art; instead they were obtained for the specific purpose of protecting art.

According to contemporaneous newspaper accounts, on the morning of the 10th of March, 1914, Mary Richardson (Fig.11) – 'a small woman...attired in a tight-fitting grey coat and skirt' – entered the National Gallery and 'stood in front of the Rokeby Venus for some moments, apparently in contemplation of it.' Then, without warning, she pulled a meat cleaver from her jacket, and began 'hacking furiously at the picture' – a painting of the goddess of love lying languidly in bed whilst gazing at herself (and perhaps the viewer) in a mirror, and the only surviving female nude by Diego Velázquez, which the National Art Collections Fund had purchased for the Gallery for £45,000 only seven years earlier. As a result of the attack, art galleries throughout London closed their doors indefinitely to the public, and immediately appealed to Scotland Yard to provide them with a means of identifying other potential vandals like Miss Richardson.

Unbeknownst to the galleries, for several years Scotland Yard had already been trying to gather photographs of criminals like Richardson: 'known militant suffragettes' and members of Women's Social and Political Union and the Votes For Women movement, who had been convicted of crimes such as damage, arson and conspiracy. At first, they attempted to collect existing photographs – such as the rather glamorous headshot of the actress Kitty Marion (Fig. 13) – or to photograph the women forcibly whilst they were incarcerated; it was later revealed that Evelyn Manesta's (Fig. 10) stiff pose and pained expression resulted from the fact that she had been violently held in place by the neck for the photograph, and that the picture had been extensively retouched afterwards, so that the arms of the police officer restraining her were absent from the final image. But because many of the women, like Evelyn Manesta, declined to be willingly photographed by the police – often closing their eyes, contorting their faces and refusing to remain still if they were forced to pose – Scotland Yard came to the conclusion that it had to resort to other means.

In September 1913, Scotland Yard's 'Convict Supervision Office' purchased a Wigmore Model 2 Reflex Camera and an 11-inch Ross Telecentric Lens, relatively small state-of-the-art equipment that enabled them to take close-up photographs of subjects from a long range. They then positioned the camera inside a prison van, parked it in the yard of Holloway prison, and hired a photographer to surreptitiously photograph the women as they took their daily exercise. In order to avoid arousing any suspicion, the prison commissioners even issued the photographer with specific code words for the job – 'photogram' for photograph, 'wild cats' for the suffragettes.

These were the photographs that were printed and copied onto identification sheets entitled 'Known Militant Suffragettes', and hastily distributed to museums and museum guards throughout London in March of 1914, along with each woman's name, age, height, hair and eye color, and previous crimes listed on the reverse. Such sheets – having only just been rediscovered in 2003, buried deep within Home Office archives – are some of the earliest artifacts of photographic surveillance that have been found to date. Yet, both their form and purpose are very familiar to us today. We commonly encounter such grids: on the 'FBI's Most Wanted' posters that hang in American post offices, on the front page of newspapers after widespread rioting and looting, and so on. In fact, the aesthetics of such photographic identity parades – the magnified and grainy images, the awkwardly tight crops, the subjects who often look elsewhere whilst unaware of the camera, and the grid itself – seem to imply criminality, menace and guilt to the contemporary viewer in a uniquely powerful way.

That said, one of the most significant changes since the suffragette movement is that, today, we have all been repeatedly photographed in this manner; we are all the subjects of surveillance on an everyday basis. Cameras line both our streets and our pockets, are perched above our computer-screens, and are tucked into nearly every corner of our offices, shops, and homes. Fleets of cars mounted with rotating cameras, and commanded by international corporations, roam across our landscape capturing 'views' of every village, town and city. Photo-enabled police vans – descendants of one which once quietly parked in the yard at Holloway Prison – sit intermittently by the sides of our roads, waiting to snap our picture as we drive by. (Throughout present-day Europe, the police often don't even stop a speeding car, but instead simply take its picture with automated speed-cameras, and send a copy of the photograph, a ticket and a bill directly to the car owner's home the next day.) And thousands of satellites orbit our planet, quite literally surveying the entirety of Earth, its inhabitants and their activities down to the very last detail. Today, we can close our eyes, contort our faces and refuse to stand still all we like; but no matter what, we will be photographed.

In light of this, another intriguing shift has occurred – particularly within the last decade or so – specifically in terms of the relationship between surveillance and fine art. Rather than being acquired for its original purposes and then relegated to a file that may lie dormant for a century, surveillance and surveillance imagery are gaining prominence within the archives of galleries, institutions and museums around the world through the artworks that they now house, exhibit, collect and preserve themselves. Artists – and particularly photographers, whose practice has always contained an element of adapting to new technologies and negotiating control over the types of images that they make– are increasingly exploring ways in which surveillance technologies and materials can be used for expressive and creative, rather than for evidential, political or authoritative, purposes. For example, in a clever twist, Trevor Paglen reverses the power dynamic between state and citizen found in the suffragette photographs, by employing today's latest telephoto lenses and turning them on the state, in order to identify and monitor his own government's known (but nevertheless clandestine and supposedly covert) militant activities. Dan Holdsworth translates and then transforms hard scientific surveillance data – gathered by government-funded, state-of-the-art satellite technologies – into vast and sublime landscapes that, in the context of the gallery, evoke within the viewer a strikingly emotional response. The immense catalogue of 'street-views' that has been gathered by Google and the like is mined, edited and diversely appropriated by artists such as Doug Rickard, Michael Wolf, Mishka Henner, and many others, as a means of not only helping us to navigate our physical environment, but to contemplate our contemporary cultural and social environments as well. And practitioners such as Joachim Schmid, Jen Davis and Osvaldo Sanviti grab intimate and telling stills from their own computer screens, whilst the private interiors, interactions, faces and lives of others are broadcast to them in real time. When it comes to surveillance, we are no longer simply passive subjects unknowingly being watched; we now explore, express and create by actively being observed, surveying each other, and even watching ourselves.

In Ways of Seeing – published in 1972, in the midst of what is often referred to as a period of 'second-wave feminism' (the 'first-wave' being the suffragette movement itself) – the art historian and critic John Berger wrote:

'A woman must continually watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself...From earliest childhood she has been taught and persuaded to survey herself continually. And so she comes to consider the surveyor and the surveyed within her as the two constituent yet always distinct elements of her identity...Women watch themselves being looked at...Thus she turns herself into an object – and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.'

As evidenced in even the most contemporary works of art – such as in Osvaldo Santivi's screen- grabbed series Le Soleil moribund, in which countless online strippers simultaneously pose and survey themselves, blatantly turning themselves into objects in the hopes of being objectified by others – Berger's argument still sadly rings true. Yet today, with the omnipresence of surveillance that is both externally enforced and self-imposed, and thrives in both public and private spheres, perhaps in some way we can all identify with Osvaldo's subjects, and the duality of Berger's 'woman'. We are all simultaneously the surveyor and the surveyed at once, continually accompanied by our own image, and forever an object of vision – a 'sight'. What the eighteen women on the suffragette identification sheets would make of this – or of Sanviti's virtual harem of twenty-first century 'Rokeby Venuses', who recline on their mattresses and gaze self-consciously at themselves through a digital mirror, as we gaze back at them from the comfort of our own bedrooms – we can only imagine. But one thing is certain; a meat cleaver most definitely wouldn't cut it.

Aaron

Schuman Photography

Copyright © Aaron Schuman, 2013. All

Rights Reserved.

This site and all of its contents may not be reproduced, in whole or in

part, in any form, without the written permission

of Aaron Schuman, and other additional artists involved in the production

of specific works exhibited on this site.